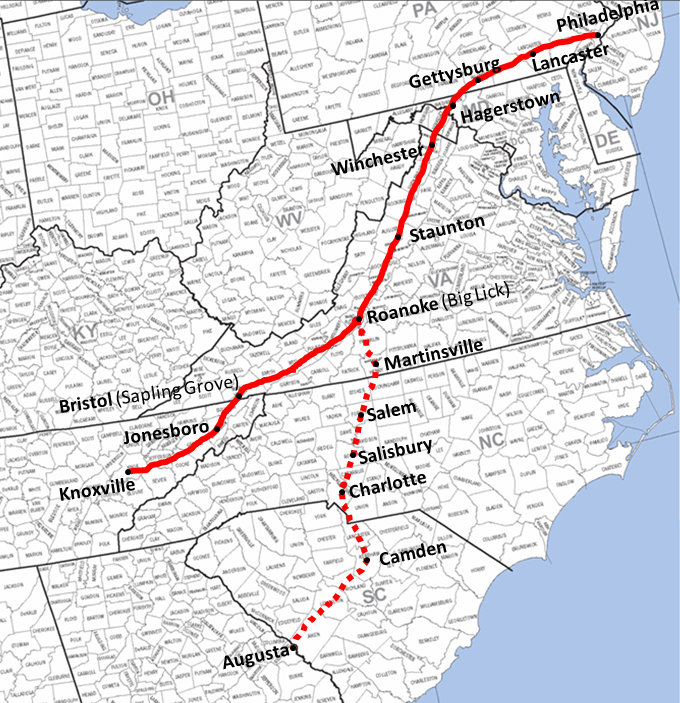

A central feature of Virginia’s colonial backcountry was the Great Wagon Road. Imagine water pouring from a pitcher, arcing as gravity pulls the liquid down into a glass. In a similar way, Scotch-Irish, German and English settlers poured down from Pennsylvania through western Maryland, filling Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, spilling into the mountains of North Carolina and eventually across the entire South.

For much of its early history, the Great Wagon Road was actually little more than a footpath, far too rugged and narrow for wagons. It was once a highway for Native American tribes raiding, trading and immigrating long before the first Europeans arrived. For this it was long known as the “Great Warriors Path.” During the colonial era, it played a crucial role for generations of new settlers in Virginia. The colony’s leaders counted on these settlers as a buffer against French and native pressure beyond the frontier. Meanwhile, they brought with them a social and economic alternative to the slavery-based tobacco plantation life central to the Tidewater region.

Among the hundreds of settlers casting their fate into the Valley of Virginia was the Ratliff/Ratcliff family – the spelling of their name was all over the place in official records. There were a number of Ratcliffs in the area at the time. In this overview of the Old Dominion’s frontier days, we’ll include a look at Reuben Ratcliff, who was born on the Maryland frontier, and what life was like for him as a settler in 1750s Virginia. There is not much known about him as an individual outside of where his 1753 freehold was located and a few details about his immediate family. We don’t know his personal stories, but we do know a fair amount about what challenges he and others like him faced in establishing a life on the edge of British America. We also know about the area’s colorful personalities, and the tragedies and triumphs they experienced that Reuben and his family would have discussed around the family hearth. Those are presented here.

Knights of the Golden Horseshoe

One of the earliest encounters that British colonists had with the Great Warriors Path was in 1716, when a group later dubbed the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe conducted its first expedition from Virginia’s capital in Williamsburg to the Shenandoah Valley. The story is celebrated in various forms today, ranging from novels and poetry, to public school awards, to U.S. Army honorifics. It’s a remarkable legacy, considering the lack of conflict or hardship that the participants experienced. By all accounts, the six-week journey proceeded at a leisurely pace, smoothed by the ample supplies and what was described as “an extraordinary variety of liquors.” A 1909 poem by the historian Robert Armistead offers the flavor of the journey, and its significance.

To horse! to horse! my gallant men,

Behold your banner flying!

The bugle shrills through wood and glen,

The echoes loud replying;

To horse, heyday!

To horse, away!

To win a fame undying.

“Come, plant the banner of our King,

Above the misty valley;

The expedition was conceived by Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood. He had recently been appointed acting governor of the Virginia colony. The proper governor, George Hamilton (1st Earl of Orkney), was rewarded the governorship in the midst of a stellar European military career, but never actually set foot in Virginia. Spotswood was eager to make a legacy-boosting move to secure “fame undying” and raise his profile in the English royal courts. He began planning the expedition in 1710, and it was launched in 1716, early in the reign of King George I. His challenge was locating a passage through the Blue Ridge to the land beyond. One feature of the Appalachian mountain range in this area is that the eastern slopes in particular are consistently steep, and the terrain offers few places where it’s possible to ride a horse or pull a carriage through the forested inclines. Locating a passage would be the first step in surveying tracts of land where settlers eager for Virginia land could find a place to settle.

The dawn is stealing down the gorge;

‘Tis not a time to dally;

The dewy prime Is stirring time.

Up, round the standard rally!”

When Spotswood thundered his command,

It needed no repeating;

With loud acclaim the close-ranked band,

Up hill, and down are fleeting.

O’er wild and waste,

In fevered haste,

The coursers’ hoofs are beating…

The group that accompanied Spotswood included about 60 men and 74 horses. Among them was a wealthy Piedmont landowner and historian named Robert Beverley. It also included two small companies of rangers and several Meherrin Indians. As they proceeded up the Rappahannock river, they stopped at one point to shoe their horses. Horseshoes were generally not needed in the Tidewater towns and settlements, since rocks were few and cobblestone streets were nonexistent. However, the mountains were rife with shale and flint, and blazing the trail could damage hooves.

And merry staves the comrades trolled,

In praise of ripe canary;

And bravoes rang through all the wold,

At mention of some fairy,

So winsome, fair, And debonair,

So wondrous coy and wary.

The lofty summit first to gain,

Each cavalier desired,

So up the steeps they swept amain,

To emulation fired.

The coursers spent,

With foam besprent,

By demone seemed inspired.

Historians are generally certain that the “lofty summit” ascended by their weary horses, foaming at the mouth in the mind of the poet, is located at Swift Run Gap. Today, U.S. Route 33 winds through the gap to one of the entrances to Skyline Drive in the Shenandoah National Park. From the heights of Swift Run to the Shenandoah River is about nine miles downhill into what must have seemed to be an edenic valley. An early account described the scene: “Spotswood and his companions beheld with rapture the boundless panorama that lay spread out before them, far as the eye could reach, robed in misty splendor.” They followed clues emblazoned on trees by Native Americans, who used the marks to follow the same route along the Great Warriors Path through the valley.

What fairer earthly Paradise,

‘Neath fabled climes enchanted,

Than where the Shenandoah lies,

‘Mid shores by beauty haunted,

An Eden blest, At God’s behest,

To western wilds transplanted!

“Now fill your flagons to the brim,

And let no hand be sparing;

Let’s pledge, my lads, a rouse to him,

Whose banner we are bearing.

Spotswood led the expeditionary team in a toast along the banks of the Shenandoah, what they called the “Euphrates,” on September 6, 1716 (nearly 11 decades after the founding of Jamestown). After a dinner where various camps consumed venison, bear, deer, and turkey, the celebrations continued. The group broke out their firearms and alcohol. The evening was spent shooting and drinking, setting off a cultural tradition practiced by southwestern Virginians to this day.

Spotswood packed an engraving iron with him, expecting to carve King George’s name on a rock to mark the occasion. However, the primary rock the company encountered was granite, too hard for the iron to make a literal lasting impression. Instead members carved their names on trees, and Spotswood buried a note in a bottle claiming the land for the king.

Yon vale we claim,

In George’s name,

Our fealty declaring.

“Undubbed by king, yet knights are we,

To sacred trust beholden;

And our insignia shall be,

A tiny horseshoe golden.

May those who climb,

To heights sublime,

In Honor’s arms be folden.”

Months after the group returned from the journey, Spotwood sent a palm-sized golden horseshoe encrusted with garnet stones to each member of the party. He dubbed the participants the “Knights of the Golden Horseshoe.” Inscribed on the horseshoe was the Latin motto: “Sic juvat transcendere montes,” or “Thus, it is pleasant to cross the mountains.” Spotswood instituted a “Transmontaine Order,” to encourage others to earn a golden horseshoe through discovery and settlement beyond the Blue Ridge. However the British government refused to pay for an ongoing supply of golden horseshoes, and the order quickly dissolved. However, the memory of the Tolkienesque journey remains today. hearkening back to the 1716 journey (even though the original group likely never set foot inside today’s state boundary). The story was revisited in a historical romance written by William A. Caruthers in 1841. On the 200th anniversary of the expedition, a revival was attempted, bestowing the knighthood on descendants of the journey and those of “worthy lineage.” This mutual admiration society died out quickly. Today, members of a U.S. Army artillery regiment also carry the insignia of a golden horseshoe in memory of the expedition. Middle and high school students who achieve the highest scores on West Virginia’s Golden Horseshoe Test of state history and culture are dubbed Knights and Ladies of the Golden Horseshoe.

Settling the Valley of Virginia

Two decades after the Golden Horseshoe journey, Robert Beverley’s son, William had his sights set on a Native American settlement called “Massanutting Town,” along the route of the horseshoe expedition. William was about 20 years old during the Golden Horseshoe journey. There is no evidence he accompanied his father on the trip, but it certainly made a lasting impression and established the horizon for the rest of William’s life. William was a full-fledged member of the Virginia elite. In 1745, his estate included 119 tenant farmers spread across five counties. His plantations included at least 61 slaves. From his headquarters at Blandfield House, he oversaw a wealth of commodity exports, including tobacco, rum and sugar.

Despite his vast holdings, he was preoccupied with settling Virginia’s interior. He wrote of his vision in 1732: “”I am persuaded that I can get a number of people from Pennsilvania to settle on Shenandore, if I can obtain an order of Council for some Land there…”

“Some land” he received: 118,491 acres about 30 miles south of the site where Spotswood had camped in the valley in late summer 1716. Obtaining the land was a bit of a scheme, played out in a similar fashion throughout the history of land distribution and settlement in America. The acting governor issued a patent for the “Manor of Beverley,” which included William and three other grantees to the acreage on September 6, 1736. The next day, each of the other three released their interest in the deal to Beverly. In this way, the business remained centralized with Beverly in full control. Today, the center of the grant is the town of Staunton.

William Beverly’s grant was among nine early grants totalling 385,000 acres in the Shenandoah Valley. Most went to Scotch-Irish grantees. This shift in nationality in the valley was remarkable given the power held by the English landowners at the core of the colony in the Tidewater region. In this way, it was decided that the Virginia backcountry would have a very different character than the tobacco plantations that filled the low country along the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay.

The German and Scotch-Irish immigrants to the valley rarely owned slaves and they often practiced faiths that dissented from the Church of England and the Reformation churches of Europe. Tobacco was not the preeminent crop in the backcountry as it was across the Tidewater. Perhaps those in power recognized that farmer-immigrants filling the mid-Atlantic ports had character and expertise better suited for settling the backcountry than the large plantation owners of the Tidewater. With respect to the Scotch-Irish, they were perhaps seen as a tough and determined vanguard to push Native American tribes out of the Valley of Virginia.

Beverly and the other oligarchs who received large grants were under a mandate to bring these settlers into the large tracts under their name. The governor required that an average of one family should be settled for each 1,000 acres of land. Just as there were shenanigans with the consolidation of the original grant, so were there irregularities in dividing up the lands. Often, larger tracts were handed to those of higher social status based on their class with little regard to those who had the money to pay for the land, but came from a lower social status.

Across social strata, there were other schemes to gain as much land as possible. In one case, an indentured servant girl named Peggy Millhollan appeared dressed as a man and used the name “John” several times to claim cabin rights (accompanied by 100 acres apiece) on the Borden grant. The scheme was discovered when a man employed to count cabins was perplexed that there were so many settlers named John Millhollan in the area. However the trick wasn’t uncovered until the land had been fully conveyed. Litigation over land was rampant to the point it was an area pastime. One lawsuit over land, Peck vs. Borden, was alive in Virginia courts for more than a century.

The Ratcliffs settle along the New River

One of those who received land patents from William Beverley was a man named John Miller. The Ulster, Ireland native conducted many land transactions in the 1740s and 1750s in the area. His dealing took him beyond the Shenandoah River to the wider Virginia backcountry, including the New River. On August 22, 1753, John Miller sold 65 acres along the New River to Reuben Ratcliff. They provide a snapshot of the struggles and modest triumphs of farmer-settlers during the early days of settlement in the Valley of Virginia. Three Ratcliffs were listed as receiving their land patents on the same date: Reuben, who settled at the confluence of the New River and Brush Creek, Samuel “Ratlive,” who settled along the New River at Meadow Creek, and Daniel Ratcliff. There is no evidence that Daniel and Samuel were related to Reuben. It seems more likely that the patent claims were being recorded more or less alphabetically, and their names fell on the same recording day. It is also likely that these Ratcliffs were working and living on the land for years before the deed paperwork was finished.

One of the important social features of those receiving grants was that gatekeepers such as William Beverley, John Miller and James Patton, did not grant patents equally. It chafed the sensibilities of those moving to the frontier that the social hierarchies that characterized English society and the rigidly stratified Tidewater were being imported to the Virginia backcountry. Many immigrants had hoped for freedom from the classism that marked the lands they had fled. A person who owned their land, a Freeholder, was a full and independent citizen. However, settlers, particularly those who were Scotch-Irish and English, had to prove their wealth or social standing in order to receive land. The wealthier and prominent received more land, and those without an established name could be in danger of acquiring no land at all.

Reuben Ratcliff seems to fall in the middle of this tension. With the exception of Reuben’s eldest brother, Richard, and two of his sisters, he and his siblings had been orphaned as youngsters. Their uncle, Richard Touchstone, held their inheritance for them until they came of age. At first glance, these young Ratcliffs had no established family from which to appeal for social status. They were also of English descent, not from the Scotch-Irish who held power in the region. Nor were they Germans with established social, religious and family networks. On the face of it, their chance of becoming independent freeholders seemed remote.

Yet, some tenuous family connections likely played a role in their ability to gain a modest foothold in Virginia backcountry society. This was due perhaps to the association the previous generation had on the Maryland frontier. Their uncle, Richard Touchstone II, had moved to southern North Carolina by the time the Ratcliffs filed claims in Virginia, but he was well-known enough among those pouring down the backcountry corridor that the boys could be vouched for as coming from a good family. The clincher may have been their family association with their uncle, Thomas Cresap, who was still pushing social and physical boundaries on the Maryland frontier. As a member of the newly formed Ohio Company, Cresap was the man-on-the-ground for fellow Ohio Company land speculators such as Virginia Governor Dinwiddie, founding father George Mason, as well as Lawrence and Augustine Washington (whose younger half-brother George later received some notoriety). Given the context, it doesn’t seem like it was a difficult decision for the gatekeeping Scotch-Irish oligarchs to allow the Ratcliff boys to become freeholders, even if the amount of land they received was too small to also warrant holding a public office that went with larger land holdings.

Life on the Virginia Frontier

The journey from Maryland’s frontier to the Valley of Virginia consisted of a six-week hike down the Great Warrior’s Path (its renaming as the “Great Wagon Road” was many years away). So, Reuben and his brothers would have carried what they owned on their backs as they wound their way from their old home in the Monocacy area of Maryland, across the Potomac and down the Shenandoah River.

Land was cheaper in Virginia than it was in the neighboring colonies to the north. In 1745 the cost of Virginia backcountry land was three pounds per 100 acres, plus the cost of surveying and administrative fees.A similar plot of land cost five times as much in Pennsylvania. A typical farm was about 50-250 acres. The settlers, all Protestants from various denominations and countries, were seen as a bulwark between the competing French and Native American populations to the west, and the wealthy tobacco plantations in the east that formed the core of Virginia wealth and power.

There were a couple of primary factors that pioneers like the Ratcliffs would look for most in choosing a place to settle: a good source of water and a strong stand of hardwood trees. While a meadow might be an attractive option with respect to the land being already cleared, the presence of a natural clearing might indicate a lack of a strong water source and the lack of trees might indicate a lack of nutrients in the soil. On the other hand, hardwood trees like red oak and chestnut provided building materials. Decades of fallen leaves and decayed roots also enriched the soil, making it ready to support crops.

The first task after moving onto the land was clearing it. The often back-breaking work included removing the trees and stumps close to the water to make room for subsistence crops. These crops included corn, beans and squash. For the first few years, these would be the main crops grown on the land, with the settler’s diet supplemented by hunting and fishing. Their housing was almost invariably a small cabin, just big enough to keep the family warm and dry. It would take two to three weeks to build, and the family would stay there about five to ten years while the farm became established. The cabin resembled log homes found in Scandinavia more than the thatched huts and other housing designs of the British Isles and Germany, where their occupants were from. The simple design included using notched logs from hardwood trees harvested from the property. Cedar shake shingles kept the rain out. The rough design didn’t require any specialized tools or knowledge. With a bit of hard work, anyone could build one without the need to pay a carpenter.One distinctive feature was a chimney that tilted away from the house. Chimneys were often constructed of stone on the lower half of the column, and wood lined with mortar or mud in the upper half. The chimney itself tilted away from the cabin and was mostly disconnected from the house itself. If, and when, the chimney caught fire, it could be easily knocked down away from the house.

The interior of the cabin was cramped, particularly so considering the large number of kids that colonial families typically raised. The little house was drafty and cold in the winter, but offered a cool refuge in the heat of summer. (The woodland Native Americans of the region had much warmer and more comfortable structures than white settlers.) Kids slept on the floor. The cabin’s loft was too smokey for sleeping, but good for storage and seasoning firewood, and drying tobacco.

There were a few cash crops that provided a significant portion of the farmers income. Tobacco didn’t hold the predominant place that it held in the Tidewater region. In Virginia’s backcountry, hemp was grown widely. This was due in part to the need for hemp ropes by the British Royal Navy. This rope was many times stronger than cotton fiber, and resisted wear even after repeatedly being wet with salt water. By 1770, farmers in the region grew nearly 300,000 pounds of hemp annually. Navy reliance on backcountry hemp resulted in a modest economic boom for the region. The settlers here also grew lots of wheat. One complaint among the dominant Scotch-Irish population was that the German settlers quickly took much of the flat lowlands near water that was good for growing wheat. Cattle were also a major source of income from the 1760s onward. In 1781, during the American Revolution, the Valley of Virginia provided the Continental Army at Yorktown about 500,000 pounds of cut and butchered beef and about 200,000 pounds of flour.

Establishing a backcountry farm was a long and difficult process. Those who took on the challenge resigned themselves to a difficult life of hard work and not a lot of security, particularly during conflicts with native tribes in the middle decades of the 18th century. Even so, it wasn’t without its joys. Music was a strong feature of the culture. When settlers first moved here, English country dance tunes were popular. Over time, those tunes faded away until cotillions and reels became popular following the Revolution. The gourd banjo emerged from instruments introduced to America by West African slaves. Violins/fiddles also took their place as popular instruments. The music took on a local flavor. While those who learned music back in Britain were trained to be precise in how they delivered their notes and melodies, the backcountry style became looser and less “reverent” over time.

Faith on the Frontier

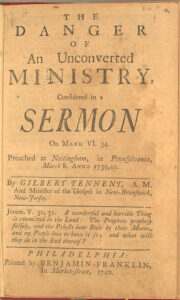

On March 8, 1740, in the village of Nottingham on the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, a Presbyterian minister named Gilbert Tennant ascended the pulpit of the town church. Tennant was wearing a block robe, and white clerical cravat from which a pair of “preaching tabs” hung to his chest. He was fresh from a preaching tour across New England with one of the leading figures of what became known at the Great Awakening, George Whitefield.

Tennant and Whitfield preached the gospel of a personal revival. A right relationship with God was through a personal conversion marked by repentance and renewed religious fervor, out of which flowed righteous behavior. Faith formed a direct connection between the believer and God, rather than the cold dogmas and a church hierarchy they observed in the high state churches. This filled Tennant’s thoughts and passions as he looked out on the congregation. His voice boomed:

“Is a blind man fit to be a guide in a very dangerous place? Is a dead man fit to bring others to life? A mad man fit to give counsel in a matter of life and death? Is a possessed man fit to cast out devils? A rebel, an enemy to God, fit to be sent on an embassy of peace, to bring rebels into a state of friendship with God? A captive bound in the massy chains of darkness and guilt, a proper person to set others at liberty? A leper, or one that has plague-sores upon him, fit to be a good physician? Is an ignorant rustick, that has never been at sea in his life, fit to be a pilot, to keep vessels from being dashed to pieces upon rocks and sandbanks.”

Tennant’s delivery and the curl of his Scottish accent grabbed the congregants’ attention. The preacher’s passion was contagious, and his argument unassailable, even if some farmers in the audience may have squirmed at the jab about “ignorant rusticks.”

“Isn’t an unconverted minister like a man who would teach others to swim before he has learned himself, and so is drowned in the act, and dies like a fool?”

With that, this historic sermon on a waypoint to the frontier split the Presbyterian church in America like an ax through a pine log. Tennant continued his theatrical and expressive polemic, exhorting those who had ears to hear that ministers that have not undergone the revival of the heart that he and other “New Light” ministers have experienced, are ill-equipped to look after the spiritual lives of those in their flocks:

What poor guides are natural ministers to those who are under spiritual trouble? They either slight such distress altogether and call it melancholy, or madness, or dawb those that are under it with untempered mortar. Our Lord assures us that the salt which hath lost its savour is good for nothing; some say, “It genders worms and vermine.” Now, what savour have pharisee-ministers? In truth, a very stinking one both in the nostrils of God and good men. They hinder instead of helping others in at the strait gate. Hence is that threatening of our Lord against them. ‘Woe unto you, scribes and pharisees, hypocrites; for ye shut up the kingdom of heaven against men; for ye neither go in yourselves, nor suffer those that are entering to go in’ (Matthew 23:13 KJV). Pharisee teachers will with the utmost hate oppose the very work of God’s Spirit upon the souls of men; and labour by all means to blacken it…”

Soon, “New Light” congregations began springing up across America, including the Virginia backcountry. The Great Awakening was sweeping across the burgeoning American culture. A key tributary among the many streams that contributed to the floodwaters that swept the thirteen colonies toward independence was a common religious feeling, grounded in individualism and self-identity. In the eyes of many Americans, as they thought of themselves, the official churches were increasingly formal, designed to enforce a distant view of God, and reinforce a social hierarchy that no longer resonated in the villages and towns an ocean away from the British centers of temporal power. Tennant’s sermon struck at just the right moment on the tension within the church and society, creating a rupture that is seen today in the split between mainline and evangelical bodies of believers. Tennant himself spent decades trying to heal the ruptures in the Presbyterian church that his sermon launched. But his message on that day carried an irrepressible idea whose time had come.

Soon, “New Light” congregations began springing up across America, including the Virginia backcountry. The Great Awakening was sweeping across the burgeoning American culture. A key tributary among the many streams that contributed to the floodwaters that swept the thirteen colonies toward independence was a common religious feeling, grounded in individualism and self-identity. In the eyes of many Americans, as they thought of themselves, the official churches were increasingly formal, designed to enforce a distant view of God, and reinforce a social hierarchy that no longer resonated in the villages and towns an ocean away from the British centers of temporal power. Tennant’s sermon struck at just the right moment on the tension within the church and society, creating a rupture that is seen today in the split between mainline and evangelical bodies of believers. Tennant himself spent decades trying to heal the ruptures in the Presbyterian church that his sermon launched. But his message on that day carried an irrepressible idea whose time had come.

The religious fervor of the Great Awakening stood in contrast to Enlightenment thinking that gripped the minds of irreligious leaders. The wealth and rationalism that fed the ideas of revolutionary thought-leaders ranging from Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Paine had a contrary effect on the people who raised the country’s wheat, wove its hemp, and harvested its tobacco. For the religiously awakened, Enlightenment rationalism and materialism seemed like an iron cage that prevented the wild heart of religious fervor from enjoying the freedom of the Spirit found in the forests, meadows and streams of the New World.

Where social rank constrained one’s social world, the Great Awakening offered God’s freedom. Repentance and piety offered a kind of liberty that was available to anyone. Out of this grew a sense of national feeling outside the old hierarchies that had survived the leveling movements of the English Civil War. The personal nature of one’s direct relationship to God worked alongside Enlightenment ideas about individual human rights in the collective imagination. The Great Chain of Being that ran one direction, from God through the monarch, to the nobles and church leaders and eventually to the peasantry was irrevocably snapped. The direct relationship New World citizens could have with their Maker was incommensurable with the cosmic order of the Old World which was ruled by divinely appointed kings.

In Virginia’s frontier, religious life was one of the most diverse in the American colonies. Those settling the backcountry came from a variety of Protestant backgrounds. This includes Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, German Reform and Lutheran adherents, as well as Aglicans. There were also burgeoning religious groups within and outside these denominational boundaries. Presbyterians were experiencing a contentious divide between the Old Side and New Side churches. Among the German settlers were pietistic and missionary-minded groups, notably the Moravians. The presence of Baptists vexed the Anglican establishment. There were also a smattering of radical groups, such as the Dunkards and others. The Great Awakening was in full swing when the bulk of settlers were moving into the Valley of Virginia. German pietists appreciated the newfound religious fervor, and their missionaries fanned out across regions where settlers were establishing their homes.

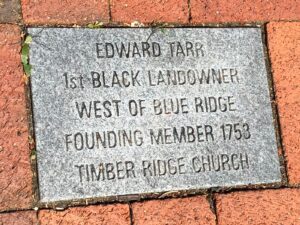

Among those who sought independence and prosperity on the frontier, as well as a vibrant spiritual life was a former slave named Edward Tarr. His story illuminated the role of Black settlers in the area, and shows the tension between the racial prejudices he encountered and the society where he had established for himself as a valued member of his community.

Freeholder Edward Tarr

In October 1753, a pair of Moravian missionaries descended from the hills about 11 miles north of what is now Lexington, Virginia. Their horses needed shoes, and they were headed to one of the few blacksmith shops in the region. It was owned by Edward Tarr, the only free black man living in the Virginia backcountry, in an area that had few slaves. His neighbors called him “Black Ned.” The missionaries wrote a glowing account of their visit. They were especially pleased with the fresh baked bread served by Ned’s wife, a Scottish woman. Virginia law had forbade marrying between the races since 1661, but there was not an explicit law against living together as man and wife once they were married. Ned and his wife (we don’t know her name), were apparently married in Pennsylvania, where he had earlier purchased his freedom. Anyone hoping to challenge their nuptials in Virginia would find themselves out of jurisdiction.

Ned’s tenure as a freeman, and a landowner or “freeholder,” in Virginia was remarkable in many ways. The Moravian brethren that visited him in the autumn of 1753, were amazed that Ned and his wife owned a pietist theology book, Berliner Reden, by Count Nicolaus von Zinzendorf, and were able to read and appreciate his theological ideas in German. Ned made the most of his freedom, including securing an education, as well as acquiring land and building a business. The Moravian missionaries observed a man whose life cut across language, religious and racial lines. Not only was Ned a relied-upon blacksmith, he also helped fund the pastorate of the (New Light) Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church, which still exists today.

The classic view of colonial Virginia, which may hold true for in areas such as the Tidewater region, was framed around the domination of the large plantation owner who relied on many slaves to work the fields and attend to the white owners’ lifestyles. The Virginia backcountry provided a much different context. In the 1750s, a well-developed culture of slavery was largely absent. There were nearly no slaves at that time in upper Shenandoah Valley, and the settlers moving into the area largely did not embrace slavery. By 1755, historians note about 44 slaves lived in the area among hundreds of farms. This would change over time.

According to a provision in his master’s will, Ned was able to purchase his freedom at the age of 37. The provision allowed for Ned to purchase his freedom over a six year period, but Ned paid it off in three. His blacksmith shop became a landmark along the immigration path along the Valley of Virginia.

The scene of Ned and his Scottish wife breaking bread and discussing pietist theology at his rural home is juxtaposed with pressure he was placed under by some of his white neighbors, including charges that he was still enslaved. The son of his former enslaver claimed in an Augusta court that he was not a free man at all. There were numerous instances in antebellum America where blacks who were rightfully free were held illegally by their enslavers, or had the courts unjustly rule against them. However, Ned Tarr was a freeholder in an area where there were (at the time) few cultural commitments to slavery. To be a freeholder was to be an economically and politically independent person recognized by law and society.

Beginning in 1759, Ned faced a series of legal troubles. Some time prior to that year, a second woman, named Ann Moore, moved onto Ned’s farm. Ann was described as a “contentious” woman, and the county courts issued an order against her for disturbing the peace. A 1761 summons for that charge, issued after Ned, his wife and Ann had moved to Staunton, referred to the woman as Ned’s “concubine.” A year later, Ann was charged with “living in adultery & Cohabiting with a negro named Nedd.” Ned wasn’t charged, nor was his “uncomplaining” Scottish wife whom the jury noted was still living in the household. Ann failed to appear in court for each of the charges. She received a small fine of five shillings for disturbing the peace, and a levy of 1,000 pounds of tobacco and a cask of wine for the morality charge, which she apparently paid. Ann remained with Ned and his wife until at least 1767, when court records indicate that she agreed to release an indentured girl from service before her contract period had finished.

Ned didn’t escape legal trouble at the time Ann Moore’s charges were making their way through the county courts. Also in 1761, Joseph Shute, the son of Ned Tarr’s former slave owner, sent a document to a man named Hugh Montgomery accusing Ned of being an escaped slave. Montgomery was apparently a relative of Ann Moore’s deceased husband. Montgomery attempted a re-enslavement fraud against Ned Tarr by claiming he had purchased Ned from Shute. Montgomery had hoped for a quick capture of Ned and a return to slavery for the blacksmith.

However, Ned countered the phony bill of sale presented by Montgomergy with a stack of papers that provided legal proof that he was free. This included Thomas Shute’s will, which allowed for Ned to purchase his freedom under certain terms, and a series of receipts that proved he had paid the price of his freedom well within those terms. Unlike Ann Moore, Ned paid close attention to his attendance on the required court dates as well as the ample documentation to disprove the claim against him.

When it came time to press his claim that Ned was a runaway slave in open court, Montgomery was a no-show. Ned showed up to the courthouse on a Tuesday, and sat waiting for his accuser throughout the day. He did it again on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. Saturday rolled around and by the end of the court session, Ned addressed the court with further documentation, and sealed Ned’s status forever with a certification that he was a free man. The magistrates presiding over the court had known Ned for ten years, and consistently referred to him as a “freeholder.” The records show that they considered him a trustworthy witness on his own behalf and a respected member of the community. His case is illustrative. Every Virginia county had free blacks. They were often protected by the courts, known in the community, and showed up in various court records. Though Ned Tarr was the only free black landowner west of the Blue Ridge, his place in society was secured through the Virginia legal culture, specifically those honoring contracts. In this particular case, the Augusta County court was loath to rule against a fully realized member of the community, regardless of his color.

Yet, Ned still faced racism in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. For example, punishment for a murder that had nothing to do with Ned or his place in Augusta life appears to have been placed by some of the county’s powerful almost literally on Ned’s doorstep. That is, a black slave named Tom was convicted of the September 1763 shooting death of Jim Harrison, a man with a legal record of abusing indentured servants. Slaves likely received no better treatment under Harrison, though the abuse was unlikely to show up in legal records. Tom was convicted and sentenced to hang by November that year, but not until the hanging was well-publicized throughout the county as a public event. The court ordered that Tom’s head “be Severed from his body and affixed on a Pole, ” and instructed the sheriff to impale his head on a pole “on the Top of the Hill near the Road that Leads from this Court House to Edward Tars.”

The placement of the head is seen by historians like Turk McCleskey as a signal to Ned that he needed to be vigilant of his own racial status, even though he had been accorded official respect and played an important role in local society. The placement of Tom’s head near Ned’s home “symbolically shackled a murderous slave to Augusta County’s most prosperous free black.” McCleskey acknowledges that the location of Tom’s impaled head might also be a coincidence, since it was intended to be placed in a prominent location, and Ned’s property ran along the main road near Staunton.

The backdrop for Ned Tarr’s wrangling of relationships, social affairs and legal challenges was the Seven Years War, and its devastating effect on the Virginia backcountry. At the time Ned was defending his freedom in the Augusta County court, the Virginia backcountry was squarely in the middle of the Seven Years War. Native American attacks and battles between tribes and Virginia militia were increasingly common. As a result, many white Virginians on the frontier fled to western Pennsylvania. At the same time, free black men consistently served in the Virginia frontier militia. Turk McCleskey remarked in a lecture that, “Even as the white guys were deserting in droves, the free black guys kept showing up. They were very reliable defenders of this frontier region.”

James Patton and Order on the Frontier

If you want to keep peace with a native Virginian

You must hold to the faith of the Ancient Dominion;

You must swear that the nobles in swarms and in droves

Forsook their ancestral castles and groves,

And collecting their crests and all portable goods,

Rose up, trussed their loins and took to the woods,

Much preferring primeval simplicity

To the plaudits of liegemen and irksome publicity…

A brace of sleek lords, score of knights, demi-gentry,

Younger sons and a deal of the best squirearchy,

Into which a strain of the yeoman found entry —

This makes the blue blood of the old oligarchy.

But I fear that to some it’s a trifle unpleasant

To learn they’re an amalgam of gentle and peasant.

But, mark ye, I speak sober truth to the letter,

More than half the peerage are not a whit better.

If you take all their forebears a cycle or two,

You will find that their blood is but tinctured with blue;

You will find a limbo of Scroggins and Tanners,

As well as the glory of Beauchamp and Manners,

I trust, gentle critic, to thus reimburse us

For the gold viewed as dross in this arrant excursus.

An idealized view of western and frontier life is that a person could arrive at the edges of civilization and become whomever they want. Hard work and force of personality were, in this poem’s romantic perspective, the only thing standing in the way of a poor man becoming rich, or the powerless gaining authority. Opening up the land brought a feeling of wide open possibilities for the future. There were many push-factors for the German, Scots-Irish, English and other settlers that moved to the west. These included economic, religious and political pressures, and even famine. But chief among the inspirational pull-factors were the twin promises of freedom and the possibility of a bright future.

This was true for some who fashioned themselves as elites, since the British culture of hierarchy exerted itself even to the colonies’ edges. James Patton (c. 1690-1755) is a prime example of someone who sat astride the power relationships in the Virginia hinterland, with one knee bent to the Tidewater elites, and another on the necks of the backcountry newcomers. The poem above by Robert Armistead Stewart alludes to the myth of how the English gentry “took to the woods.” This myth was alive in the early days of the backcountry, and some knew how to use it to their advantage. Among them was James Patton.

Patton was a dominating character in the Virginia backcountry, claiming a place of distinction among many strong-willed and well-connected grantees in the Valley of Virginia. He is similar to Maryland’s Thomas Cresap in that he relentlessly chased his vision of carving out the edges of a colony for new settlement. One big difference between Patton and Cresap was that Cresap was ready and eager to sow chaos when he felt it was needed to achieve his vision for an enlarged Maryland. Patton, however, set his sights on becoming the catalyst of order on the edges of Virginia. This doesn’t mean that Patton lacked Cresap’s will. Rather, he used his savvy human understanding, a penchant for off-the-record deals, and his position as a landowner and officeholder as leverage to achieve his goals and to secure his position as a rising star in the Virginia colony.

Success of men like Patton, and others such as Lewis, Buchanan and Beverley depended on the sponsorship and approval of the elites in the Tidewater. Though they largely weren’t English, they were familiar with the English-dominated administration of the British periphery. Namely, northern Ireland. As traders and administrators, they knew how to navigate the halls of power and foster trust from the elites to secure a place in the frontier order long before they set sail for the New World. James Patton was the poster child for this kind of erstwhile leader.

Around the year James Patton was born, his father received an allocation of land in Ulster for fighting on the side of King William III against James II and his Irish Catholic allies. As early as 1719, Patton pursued his fortunes at sea as a ship owner and captain. In the decades before he became a major power broker in the Virginia backcountry, he was a merchant ship captain based in southern Scotland smuggling tobacco and other merchandise across the Atlantic for an English partner. He also shipped trade goods from the English colonies and Mediterranean. During a shipwreck and looting incident in 1729, Patton displayed the same pugnaciousness he would later employ on the frontier. During this incident, Patton’s ship, the William, ran aground on a sand bar along the coast of Cornwall. Those living nearby often took advantage of ships stranded on the “Doom Bar.” They would row out to the stranded ship, wreck it by cutting cables and otherwise making it unseaworthy, then take the goods that the ship was carrying. Patton was reported as fending off the Cornish looters by force of arms:

“Letters from Padstow in Cornwal, of the 17th of Nov. [1729] advise, that the William of Dumfries, Capt. James Patton, was drove on a sandy Bank there, on the 14th, after having suffered much Damage at Sea, and for some Time was without any Hopes of saving their Lives; and the Tide ebbing, and leaving the said Bank dry, the Inhabitants seeing this Prize, sallied out in great Numbers, and began to cut and hew the Ship and Tackle, till the Captain being well provided with Fire Arms, by an uncommon Bravery threatned to discharge them among the Rabble; whereupon many of them dispersed, till he got Time to secure Part of his Cargo, which was much damaged, but was still in Fear of being overpowered by the Mob, and without any Hopes of saving his Ship.”

As a merchant and smuggler, Patton undoubtedly developed some of his most useful skills for behind-the-scenes dealmaking and developing powerful relationships with those who wielded power at some distance from him, often infuriating those who dealt closely with him. This includes his English partner and owner of the ships Patton sailed, Walter Lutwidge, who was noted for his own dubious dealings. This included transatlantic slave transportation. (There is no direct evidence of James Patton transporting slaves.) In a conflict with Lutwidge over Patton’s duplicitous behavior toward his employer, it appears that Patton won the argument by threatening to expose Lutwidge’s own shady relationships with customs officials in Virginia and England. By the time the Patton-Lutwidge conflict reached its climax, Patton had already prepared an escape to the Virginia frontier. A letter from Lutwidge to a colleague on Virginia’s western shore speaks to the ire that Patton could conjure from his close associates:

… I have mett wth Boath Knaves and fooles in plenty and but few Honest Industereus men, but of all ye Knaves I Ever mett with Patton has out don them all. James Concannan can tell [you of] his viloney wch I dare not repeat, he chargd no Less then 6000 lb of fresh Beef in Virga [Virginia] 40 Barrs [barrels] Indian corn and Evry thing Else in proportion, took 15 Serts [servants] to him self att a clap. In short Hell itself cant out doe him” (Letter to James Johnson at a tobacco port on the western side of the Chesapeake Bay, 24 December 1739).

As Patton’s maritime career was being run aground and his reputation in danger of being looted of its remaining value, he was working within the circles of Virginia’s elite to launch a second career. Two years after Lutwidge’s scathing correspondence about Patton’s arrogance and lack of honesty, Patton emerges onto the scene as one of Virginia’s elite landowners. In August 1737, William Beverly of the Blandfield Plantation, one of the richest landowners and office-holders in Virginia, sent Patton two letters regarding the settlement of land on Virginia’s frontier. Beverley had been granted 30,000 acres, and offered Patton one quarter of the land “if you could import families enough to take the whole off from our hands at a reasonable price and tho’ the order mentions families from Pensilvania, yet families from Ireland will do as welL”

The 1737 letters are indicative of a few things. First, the rich and powerful Beverley addressed Patton as an equal. It appears that James Patton lived a double life. Among the Scottish and English sea traders, he was known for his bad temper and dodgy business dealings. In Virginia, however, he was treated as fellow gentry. Like many who came to the New World, Patton appears to have been cultivating the start of a new life among the colony’s ruling families. It also explains Lutwidge’s complaint that Patton was charging exorbitant amounts of foodstuffs (6,000 pounds of beef, 40 barrels of corn, etc.) and employing 15 servants at Lutwidge’s expense. Patton was seemingly lifting himself up by Lutwidge’s bootstraps.

To the Virginia powerbrokers, Patton played the part of a rich trader who deserved the deference and opportunity reserved for society’s privileged. During this time imported the first thoroughbred horse, named Bully Rocke, which launched the tradition of American horse breeding. At the time, Patton was striving to come across as minor aristocracy who would forsake his “ancestral castles and groves” to become one of the backcountry’s chief power brokers. Often, stories of those who attempt to pull off such a ruse follow an arc of some success followed by a crash back to their more or less humble beginnings. Yet, Patton appears to have successfully pulled it off, at least until his brutal death in 1755.

One of the gifts of Patton’s personality was his ability to work out deals in the background that paid off richly in both wealth and reputation. An early example is in the Beverley letters of 1737. The letters are written with an informality that implies a burgeoning relationship between the two men that had been cultivated for some time off the record. Beverley trusted Patton, and the two had a friendly and astonishingly lucrative business relationship. Beverley formed a similar partnership with another ambitious Scotch-Irishman with a questionable background, John Lewis (1678-1762), who happened to be Patton’s uncle by marriage. Lewis had recently fled northern Ireland after killing his abusive landlord with a shillelagh walking stick over a rent dispute, for which he was later pardoned.

In 1739-1740, Patton made his final two voyages as a merchant captain for Lutwidge’s ships. He took a delivery of Virginia tobacco to Holland, upon the sale of the crop to Dutch merchants, he procured a shipload of European goods (linen, iron, wool and timber) and sailed back to England. This appears to have provided enough solvency for his next act as a frontier land baron and agent. By 1745, the business partnership of Beverley, Patton, and Lewis accounted for nearly 77 percent of all land transfers to first-time freeholders in the Virginia frontier. In 1748, Patton and Lewis formed the Loyal Land Company of Virginia with Dr. Thomas Walker. This company was soon granted 800,000 acres, with the stipulation that they survey the enormous tract within four years, and begin sales to new settlers moving into the area.

In the ensuing years, Patton’s business relationship with his uncle, John Lewis, began to strain. Patton had formed his own Woods River Company, and laid claim to another 100,000 acre grant. The two became rivals over the amount of power and wealth each controlled in the formative years of Virginia’s Augusta County. The first Presbyterian minister west of the Virginia’s Blue Ridge, Rev. John Craig, recalled the animosity between the two: “Their disputes ran so high…I could neither bring them to friendship with each other, nor obtain both their friendships at once, ever after.”

Contentiousness wasn’t confined to the squad of land barons that included Patton, Lewis, Beverley and Benjamin Borden. Patton seemed to attract strong negative feelings across the social spectrum, yet always seemed to be one step ahead of his opponents. This did not extend to the Virginia’s Tidewater elites, who bestowed ranks upon Patton and his associates, and endorsed their decisions over how frontier settlement was carried out.

Over the years, Patton held a variety of positions: Justice of the Peace, sheriff, county coroner, magistrate, colonel and chief commander of the Augusta County militia, member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, among other positions. However, his chief role in the 1740s was in the settlement of newcomers on lands granted to him and his partners. By 1745, more than 75 percent of transfers to first-time freeholders was controlled by Patton and his partners Lewis and Beverly. Actually receiving the land was difficult. In the early 1740s fewer than half of those who attempted to settle on the grants successfully received a deed. Among those who received a land patent, the average wait was eleven years to gain title from Patton and his associates.

Though elites like Beverly, Border and others accepted Patton as a peer and valuable partner (and sometimes worthy rival) in brokering power in Virginia’s backcountry, those moving into the area where Patton remained the de facto boss seemed to see through his pretense as coming from the top of society. Many seemed to say to themselves, “who is this man who sets himself above us.” They saw him as a rogue and pretender, with rumors he was even a pirate in his former career. Entwined in their dissatisfaction was their mistaken assumption that the immature economic structure of the area also meant that the societal hierarchy was not fully formed. In fact, it was firmly enforced by Patton and his partners. The colony’s elites enlisted Patton and those like him to enforce the hierarchical structure of society in order to avoid chaotic breakdowns in society experienced by Virginia’s neighbors. Thomas Cresap’s war between Pennsylvania and Maryland not only sowed chaos, but it also often witnessed insults to those in the upper classes spewed by mere commoners. Virginia saw to it that territorial growth was achieved without social upheaval, and they viewed Patton as the man who could get this done. This doesn’t mean he didn’t face personal challenges.

In 1748, a destitute man named Robert Hill told a crowd assembled outside the courthouse that Patton “was a sorry fellow” not worthy to wipe Hill’s shoes after a friend of his had been “unjustly” jailed. For the outburst, Hill received a jail sentence of his own. In 1754, John Grymes, who owned 400 acres of land, first called Patton a fool during a court proceeding. This earned Grymes a fine of five pounds sterling. Grymes couldn’t control his fury at Patton when the court was recording the fine, and further called Patton a “whoresbird, etc.” (son of a prostitute), which directly challenged Patton’s purported elite lineage. For this, his fine was increased to 25 pounds sterling. Before it was over, Grymes faced another 200 pounds sterling for his challenges to Patton. There were other cases where those who insulted the court faced penalties. Notably, those of lower social status faced time in the stocks and full payment of their more modest fines. Though Grymes was among the worst offenders when it came to insulting Patton (and therefore the court he presided over), he was able to avoid time in the stocks, and later begged Patton’s forgiveness, ultimately avoiding any payment.

Patton’s rivalries included attempts to keep other large landowners off the county judicial benches. He even harbored suspicion of Lord Fairfax. Despite his occasional political setbacks, he was mysteriously able to rout his competitors and come out on top in the Augusta County power games, even pushing Lord Fairfax’s interests out of Augusta county government on one occasion. Yet, his ability to keep the peace and keep settlers moving in outmatched his tendency to rub people the wrong way. Along with his land grant work, Patton had numerous encounters with native tribes that helped maintain order in the Valley of Virginia. This includes his presence at the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster. He wasn’t a signatory, but he participated in the plan that paid the Six Iroquois Nations four hundred pounds in exchange for which the tribes renounced their claims in Virginia. The treaty provided “a marked path up the Valley,” which, as the commissioners stated, “shall be the established Road, for the Indians our Brethren of the Six Nations, to pass to the Southward, when there is War between them and the Catawbas.” This treaty provided the groundwork for the transition of the Great Warriors Path into the Great Wagon Road that would bring thousands of immigrants from Pennsylvania, through Maryland, and into the South. Construction of the first section of the road, the Valley Pike (today’s US 11), was soon underway.

In 1751, Patton took a delegation of Cherokees to Williamsburg. The tribe was experiencing the impracticalities of long trade routes and high prices commanded in the Carolinas. They came to Patton’s territory looking for shorter routes and more favorable terms. After several weeks of negotiation facilitated by Patton, acting Virginia governor Lewis Burwell and Cherokee chief Attakullakulla were able to work out a trade agreement with the tribe. Patton escorted the Cherokee delegation home to the area around the Tennessee border, a journey of about 30 days.

Patton continued administrative efforts to make sure relations with the Cherokee and Iroquois tribes remained stable. This required Patton, one of the strongest personalities on the Virginia frontier, to interact with his feisty Maryland counterpart, Thomas Cresap. In true form, Cresap at one point accused Patton of attempting to obstruct his plans to create settlements with the Ohio Company, which Cresap had invested in. Governor Dinwiddie told Cresap that he was surprised by the accusation, and reassured Cresap that the Ohio Company’s planned expansion of the frontier was safe from Patton’s ambitions under his watch.

Upheaval and Violence on the Frontier

Despite his domination of Virginia’s backcountry politics, economy and society, there were forces larger than the formidable James Patton that would lead to his violent demise. In 1755, tensions had evolved into violence between native tribes and the British colonies. The French had expanded their power into the Ohio River valley, and allied with Native American tribes to oppose the British. The assertion of French power included the establishment of Fort Duquesne at the present site of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1754. The following year, the British suffered an embarrassing defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela, in which General Edward Braddock was mortally wounded. The French and Indian war was now in full swing. The weakened position of the British meant that native tribes raided unprotected British farms and settlements with impunity along the edges of the colonies.

Dinwiddie had awarded the 7,500 acre Draper’s Meadow to Patton in 1753. The land is currently situated in the area of the duck pond on the campus of Virginia Tech in Blacksburg. The land already had settlers, including John Draper who had moved there in 1746 and William Ingles who came four years later and married Draper’s daughter, Mary. Patton sold them the land that they had each been working for years.

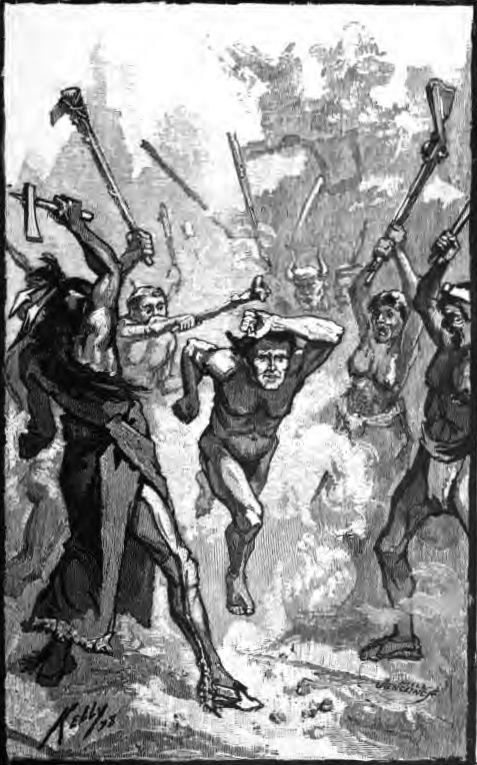

On July 30, 1755 a group of sixteen Shawnee warriors, allied with the French, entered the settlement. Most of the men were working the harvest in the field. The women, children and the elderly were in the settlement. The raid resulted in the deaths of four people: an elderly man named Caspar Barger, John Draper’s wife (Mary Draper Ingles’ mother) Eleanor, and her sister-in-law Bettie’s infant daughter. Bettie was wounded by a shot through the arm, and another man was shot in the foot. Mary Draper Ingles and several others, including two of her sons, were captured. James Patton was killed. Reports said that he was shot, scalped, and his body was so mutilated that it was buried near where he fell. His hasty grave was covered with loose stones, and no marker was placed at the site. His burial was desecrated a number of years later by those looking for coins that were reportedly sewn into the clothing that he was wearing at the time. The brutality of the raid was recorded by Letitia Preston Floyd, whose father William arrived at Draper’s Meadow shortly after the attack:

…It being a Sunday a party of Indians came up the Kanawha, thence to Sinking Creek, thence to Strouble’s Creek – Inglis & Draper, brothers in law, were living at Solitude, the present seat of Col. Robert T. Preston. The Indians came to Barger’s (1/2 mile nearer the Mountain) & cut his head off & put it in a bag; Barger was a very old man then came to Inglis’ and Drapers, and killed old Mrs. Draper, two children of Col. Inglis’, by knocking their brains out on the ends of the Cabin logs – took Mrs. Inglis and her sister-inlaw Mrs. Draper Jr., who was trying to make her escape with her infant in her arms, but she was shot at by the Indians, who broke her arms by which means the infant was dropped – the Indians picked the infant up, & knocked its brains out against the Cabin logs.

Col. Patton that morning having dressed himself in his uniform, and getting his nephew William Preston to sew up in the fob of his small clothes thirty British guineas, told him to go to Sinking Creek to get Lybrook to help take off the harvest; which was then ready to cut; Preston went very early – After breakfast, Col. Patton sat down to write, the Indian war whoop was heard and five or six of them surrounded the cabin to set it on fire – The Col. Always kept his sword on his writing table – he rushed to the door with it in hand and encountered the Indians – Patton was almost gigantic in size – he cut two of the Indians down – in the meanwhile another warrior had leveled his gun and fired and killed the brave old pioneer – After Patton fell the Indians ran out in the thicket and made their escape before any pursuers could be brought together.

Lybrook & Preston came through the mountains by an unfrequented route, having arrived at Smithfield they found Col. Patton, Mrsl. Draper (the mother of Mrs. Inglis) & the (three) children, (and) buried (them); The whole settlement was destroyed. The Indians on their return stopped at Lybrook’s, and told Mrs. Lybrook that they had killed two men, one woman and three children, and requested her to look in the bag that they had brought with them, and she would see an old acquaintance, she did so, and immediately recognized the head of Barger who was a very old man.

Mrs. Inglis, her oldest son a lad of ten years of age, & Mrs. Draper her sister-in-law, were taken to the Indian towns on the other side of the Ohio River, they travelled down the Kenawha of as it is sometimes called New river, & through the North eastern part of Kentucky.”

“A woman of no ordinary nerve”

After the attack at Draper’s Meadow, 23-year-old Mary Ingles, her two sons, four-year-old Thomas and two-year-old George, and her sister-in-law Bettie Draper were taken by the Shawnee on a long journey to Kentucky. William Henry Foote, a Presbyterian minister and historian of the region recounted her ordeal based on Mary’s stories and those of their peers and family:

The captors were partial to Mrs. Inglis, and having several horses permitted her to ride most of the way and carry her two children. Mrs. Draper, who was wounded in the back and had her arm broken in the attack upon the settlement, was less kindly cared for. As usual all the prisoners suffered from exposure, and privations, and confinement on their march. Mrs. Inglis had more liberty granted her than Mrs. Draper. The Indians permitted her to go into the woods to search for the herbs and roots necessary to bind up the broken arm and the wounded back of her fellow captive, trusting probably to her love for her children for her speedy return.

They kept the little boy of four years, and his little brother of two, as her hostages. She stated afterwards that she had frequent opportunities of escaping while gathering roots and herbs, but could never get her own consent to leave her children in the hands of the savages, and was always cheered by the hope of recapture or ransom. When the party had descended the Kenawha [River] to the salt region, the Indians, as was usual, halted a few days at a small spring to make salt. After about a month from the time of their captivity the party arrived at the Indian village at the mouth of the big Scioto. The partiality for Mrs. Inglis exhibited by the captors, during the march, was more evident upon reaching the village. She was spared the painful and dangerous trial of running the gauntlet; while Mrs. Draper with her wounds yet unhealed was compelled to endure the blows. When the division of the captives took place, Mrs. Inglis was subjected to the great trial of being parted from her children, and prohibited the pleasure of inter[action] with them, or even of rendering them any assistance.

John Ingles, Mary’s son, wrote about the gauntlet the captives endured: “The next day after they got to the nation, the prisoners had to undergo the Indian custom of running the gauntlet, which was performed by forming a two lines of all the Indians in the nation, men, women, and children, and the prisoners to start at the head of the two rows formed, and run down between the lines, and every Indian giving them a cut or a pelt with switch sticks, or such things as they could provide; which was a very severe operation, and especially on my Aunt Draper, whose arm had not got near well from the wound she had received when she was taken prisoner.”

[While] some French traders from Detroit were visiting the village with their goods, Mrs. Inglis at her leisure moments made some shirts for the Indians out of the checked fabrics. These were highly prized by [the Shawnee] as ornaments, and by the traders as a means of a more rapid sale of their articles, at a high price; and both waited on the captive to exercise her skill as a seamstress. When a garment was made for an Indian, the Frenchmen would take it and run through the village, swinging it on a staff, praising it as an ornament and Mrs. Inglis as a very fine squaw; and then make the Indians pay her from their store at least twice the value of the article. This profitable employment continued about three weeks; and the seamstress besides the pecuniary advantage secured the admiration of her captors. Mrs. [Bettie] Draper’s wounds prevented her from sharing in the employment or advantage, she was held in less estimation, and employed in more servile offices.

Mrs. Inglis was soon separated entirely from Mrs. Draper and the children. A party setting off for the Big Bone Lick [named for the large salt deposits used by animals and the exposed fossilized remains of Mammoths nearby], on the south side of the Ohio River, about 100 miles below, for the purpose of making salt, took her along, together with an elderly Dutch woman captured on the frontiers, and retained in servitude. This entire, and in her view, needless separation from her children, prompted by a desire to wean them from the mother, brought her to the determination of attempting an escape…After mature consideration, she resolved to make the attempt to reach home, preferring death in the wilderness to such captivity.

She prevailed upon the old woman to accompany her in the flight. The plan was to get leave to be absent a short time; and proceed immediately to the Ohio River, which was but a short distance from the Licks, and follow that river up to the Kenawha, and that river to New River, and so to the meadows, or some nearer frontier. They must travel about one hundred miles along the Ohio before they passed the village at the mouth of the Scioto, and consequently be in danger hourly of the severities that might follow a recapture. Their resolution was equal to the danger and trial. They obtained leave to gather grapes. Providing themselves each with a blanket, tomahawk, and knife, they left the Licks in the afternoon, and to prevent suspicion took neither additional clothing nor provisions. When about to depart, Mrs. Inglis exchanged her tomahawk with one of the three Frenchmen that accompanied the Indians to the Licks, as he was sitting on one of the Big Bones, cracking walnuts.

They hastened to the Ohio [River], and proceeded unmolested up the stream, and in about five days came opposite the village at the mouth of the Scioto. Here they found a cabin and a cornfield, and remained for the night. In the morning they loaded a horse, found in an enclosure nearby, with as much corn as they could contrive to pack on him, and proceeded up the river. In sight of the Indian village, and during the day within view of Indian hunters, they escaped observation, and passed on unmolested.

It is not improbable their calm behavior, and open unrestrained action, prevented suspicion in any keen-sighted [Native American] that might have seen them from the village, as they were plucking the corn and loading the horse. This route being on the south side of the Ohio, was unexposed to [Indian] interference, except an occasional hunting-party, and none of these crossed their track after they left the mouth of the Scioto.

[Later, the Shawnees reported that] the party at the Licks became alarmed at the prolonged absence of the women, and hunted for them in all directions, and discovering no trail or marks of them whatever, had come to the conclusion that they had become lost, and wandering away, had been destroyed by the wild beasts. There had been no suspicion of any escape, the difficulties in the way had appeared so insurmountable ; on the north side of the Ohio were the Indian tribes and villages, and on the southern side, obstructions too great, above Kentucky, to encourage hunting-parties, or permit war paths. It seemed to them impossible, that two lone women, unprovided with any necessaries for a march, or arms for defense or to obtain provisions, could possibly have accomplished so uninviting a journey. The fugitives traveled with all the expedition their circumstances would permit, using the corn and wild fruits for food.

Although the season was dry, and the rivers low, the Big Sandy was too deep for them to cross at its entrance into the Ohio. Turning their course up the river for two or three days, they found a safe crossing for themselves on the drift-wood. The horse fell among the logs and became inextricable. Taking what corn they could carry, they returned to the Ohio, and proceeded up the stream. Wherever the water courses that enter that river, were too deep for their crossing at the junction, they went up their banks to a ford, and returned again to the Ohio, their only guide home.

Sometimes, in their winding and prolonged journey, they ventured, and sometimes were compelled to cross the crags and points of ridges that turned the course of the rivers with their steep ledges; but as speedily as possible they returned to the banks of the Ohio. The corn was exhausted long before they reached the Kenawha; and their hunger was appeased by grapes, black walnuts, pawpaws, and sometimes by roots, of whose name or nature they were entirely ignorant.

Before they reached the Big Kenawha, the old Dutch woman, frantic with hunger and the exposure of the journey, threatened the life of Mrs. Inglis, in revenge for her sufferings and to appease her appetite. On reaching the Kenawha, their spirits revived, while their sufferings and exposures continued, and their strength decreased. Day after day they urged on their course, as fast as practicable, through the tedious sameness of hunger, weariness, and exposure by day and by night; yet unmolested by wild beasts at night, or the [Native Americans] by day.

When they had gotten within about fifty miles of Draper’s meadows, the old woman in her despondency and suffering, made an attack upon Mrs. Inglis to take her life. It was in the twilight of evening. Escaping from the grasp of the desperate woman, Mrs. Inglis outran her pursuer, and concealed herself under the riverbank. After a time she left her hiding-place, and proceeding along the river by the light of the moon, found the canoe in which the Indians had taken her across, filled with dirt and leaves, without a paddle or a pole near. Using a broad splinter of a fallen tree, she cleared the canoe, and unused to paddling contrived to cross the river.

She passed the remainder of the night at a hunter’s lodge, near which was a field planted with corn, but unworked and untended, and destroyed by the buffaloes and other beasts, the place having been unvisited during the summer on account of the [native] inroads. In the morning she found a few turnips in the yard which had escaped the wild animals. The old woman, on the opposite side of the river, discovered her, and entreated her to recross and join company, promising good behavior and kind treatment. Mrs. Inglis thought it more prudent to be parted by the river.

Though approaching her former home, her condition seemed almost hopeless. Her clothing had been worn and torn by the bushes until few fragments remained. The weather was growing cold; and to add to her distress a light snow fell. She knew the roughness of the country she must yet pass; and her strength was almost entirely wasted away. Her limbs had begun to swell from wading cold streams, frost, and fatigue. Traveling as far as possible during the day, her resource at night was a hollow log filled with leaves.. She had now been out forty days and a half, and had not traveled less than twenty miles a day, often much more.

In this extremity she reached the clearing made in the spring by Adam Harman, on New River. On reaching this clearing, seeing no house or any person, she began to hallo. Harman and his two sons, engaged in gathering their corn and hunting, were not far off. On hearing the hallo, Harman was alarmed. But after listening a time, he exclaimed, “Surely, that is Mary Inglis!” He had been her neighbor, and knew her call, and the circumstances of her captivity. Seizing their guns, as defense if the Indians should be near, they ran and met her, and carried her to their cabin; and treated her in a kind and judicious manner.

Having bathed her feet, and prepared some venison and bear’s meat, they fed her in small portions; and the next day they killed a young beef, and made soup for her. By this kind treatment, she found herself in a few days able to proceed. Mr. Harman took her on horseback to the Dunkards’ Bottom, where there was a fort in which all the families of the neighborhood were gathered. On the morning after her arrival at the fort, her husband and her brother John Draper came unexpectedly. They had made a journey to the Cherokees, who were on friendly terms with the Shawnees, to procure by their agency the release of the captives. On their return they lodged about seven miles from the Dunkards’ Bottom, in the woods, the night Mrs. Inglis reached the fort. The surprise at the meeting was mutual and happy. Thus ended the captivity and escape, embracing about five months. Of this time, about forty- two and a half days were passed on her return.

Foote recounts Mary’s insistence that Harman and his sons locate the Dutch/German woman that she had escaped with. Harman was reluctant to do so, given the attacks and potential for cannibalism that the woman had displayed. They knew the woman would soon come across a cabin on her side of the Ohio River. To assist, but also keep their distance, they prepared a kettle of venison and bear’s meat, and left the cabin before she arrived. They also left the woman some clothing and a horse to assist her return. The woman, whose name is not recorded, reached the fort at Dunkard’s Bottom, where Mary Ingles was also staying. Mary Ingles then moved to Vause’s Fort near the head of the Roanoke River, and moved again to take up residence east of the Blue Ridge. Not long after she and her husband left Vause’s Fort, a force of both French and Native Americans made a surprise attack on the fort and murdered or made prisoners of all the families.

The French and Indian War continued to take its toll on Virginia’s frontier settlements. The Ratcliffs saw troops marching through their farms in search of hostile tribesmen more than a year after the Draper’s Meadow attack. A militia captain recorded in his journal:

“We followed the sd : Creek down to Little River, and crost the Little River & went to Francis Easons’ Plantation where we continued that night. Our hunters brought a plentiful supply of Venison— Next morning being tuesday the 15 Inst, we marct. down to Richard Rattlecliffs’ plantation on the Meadow Creek, where we continued that night — Next morning being Wednesday the 16th. Inst, we Sent our Spyes and hunters to Spy for Enemy Signs, & to hunt for provisions. But the body of the Company Tarryed there — At Night they came in with a plenty of Venison, but could not dis- cover any fresh sign of the Enemy — Next morning Thursday the 17th Inst, we sent out hunters as usual, & in the afternoon some of them came in & informed us that they had seen signs of Indians at Drapers’ Meadow, that had been a catching of horses that Day, and that they had gone a straight course for Blackwater …”

An officer named Major Andrew Lewis wrote to Lt. Gov. Dinwiddie in late June 1756 of the aftermath he observed following the Native American raids on British settlements: “To See the Mothers with a train of helpless Children at their heels stragling through woods & mountains to escape the fury of those merciless Savages to see Sundry Persons crawling home with Arows sticking in Several Parts of their Bodies which with the Cries of Widows & Fatherless Children is really Shocking”

Altogether, William and Mary Ingles had six children, two before the Draper’s Meadow massacre and four afterward. George, who was two when he was captured, died in captivity. His elder brother by two years, Thomas, remained with the Shawnee for thirteen years. William Ingles asked an intermediary to find and purchase his son from the Shawnee, which he successfully did for $150. Thomas’ separation from the tribe was difficult. He spoke no English. During his first night away from the tribe, he escaped back to their encampment and remained hidden for another two years.

His father learned again of his possible location, and took kegs of rum to the tribe as a means of learning Thomas’ whereabouts. As the evening wore on, the now-inebriated men of the tribe wanted to kill William Ingles, but the women of the tribe implored them to let him go. WIlliam learned that his son was far to the north, in Detroit. Thomas and his old Indian father returned to the area, and William had stayed nearby in case his son returned. Thomas was reportedly touched that his father was there, and indicated that he was willing to finally go home with him. After paying a second ransom, WIllian Ingles and his son Thomas returned to the Ingles family home. Afterward Thomas did not show any desire to return to his tribal family.