At the time of writing, Great Britain is mourning the death of Queen Elizabeth II. It seems like a good time to take stock of family connections across the pond. Specifically, the origins of the name and the family in England.

Most Ratliff histories that I’ve encountered over the years offer few details about the “Tower Radcliffes” when speaking about the family’s origins. Here, I delve a bit more into the deep history of the family and the name, including who exactly the Tower Radcliffes and their descendants were prior to the migration to America. By all accounts, Ratliffs and Ratcliffs in the United States were largely descended from yeoman farmers from the countryside rather than the aristocrats who occupied the manors. The stories here show how the lives of the Tower and Ordsall Hall Radcliffes in England bear directly on the American family’s history. I think these stories are worth embracing as part of the larger family heritage, and interesting on their own merits.

A Note on Name Spellings

Radcliffe is the standard spelling used most in history books about the village and tower along the banks of the River Irwell, as well as the family that rose to prominence there. However, there is evidence that the “Radcliffe” spelling was used concurrently with “Ratcliffe,” “Ratliff,” and other variations for hundreds of years. For example, in the play Richard III, written by William Shakespeare between 1592 and 1594, Sir Richard “Ratcliffe” is presented as loyalist and executioner for the play’s main character. The character introduces the world to the phrase “short shrift.” Shakespeare likely took the name spelling from the history book, The Chronicle of Jhon [sic] Hardyng in Metre, published in 1543 that includes individuals most often referred to in English histories as “Radcliffes.”

Salford Hundred in Lancashire by John Speed (1610)

It was long thought that the name “Ratliff” was relatively new, perhaps originating on the American frontier. However, the name “Ratlif,” without the “d,” “c,” or “e” appears on John Speed’s 1610 map of Lancashire for the place name of Radcliffe, home of Radcliffe Tower.

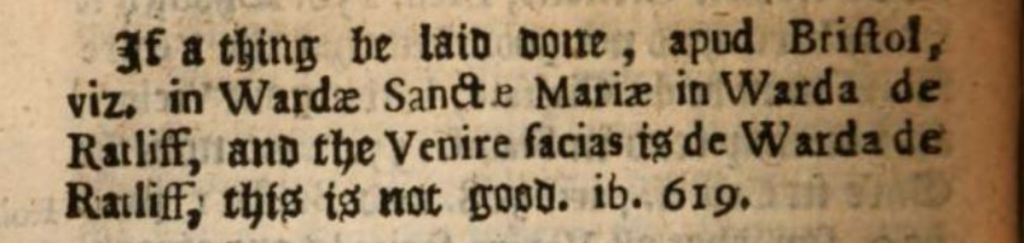

The red sandstone cliffs that inspired the Radcliffe name contributed to similar names all around England. This includes: Radcliffe-on-Trent, Ratcliffe-on-Soar, Ratcliffe on the Wreake, Ratcliff (Stepney), and Radclive (Buckinghamshire). It also includes the church of St. Mary Redcliffe in Bristol, which Queen Elizabeth I called “the fairest, goodliest, and most famous parish church in England.” The ward in which this church is located was referred to in the 1680s as the “Ward of Ratliff.” This is likely an example of how local pronunciations can cause a drift in how names are spelled and said, particularly in a time without standardization.

“Ward of Ratliff” in Tryals per Pais, or the Law of England concerning Juries by Giles Duncombe (1682)

Probate document signed in Conococheague Manor, Maryland (1741)

The name variations show up several decades later in colonial America in a similar configuration when Richard Ratcliffe signed a deed as “Ratlief” in Talbot County, Maryland in 1695. Name spellings seem to go off the rails once the family reaches the frontier, where literacy itself was in retreat. For example, the eldest son of one of the earliest documentable ancestors in America signed his name “Rattleiffe” on official documents, but the same person shows up in other official records variously as Ratliff, Ratcliff and Ratcliffe.

The family seems to have permanently shed the extraneous letters in Virginia following the American Revolution, emerging from the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky as simply the “Ratliffs.” One could make the argument that the “Ratliff” examples from 1610 onward may reflect how the family name was commonly spoken through the centuries, while Radcliffe and Ratcliffe indicate how it was nobly pronounced, or at least preferred in some official documents.

The Tower Radcliffes

Ground Zero for the family is a beautiful, ancient parish church and a tumbledown ruin of a fortification a little over two miles south of the modern town of Bury, Lancashire. Radcliffe Tower was the home of James de Radcliffe who rebuilt it over a previous structure in 1403. Twenty-first century archaeological work at the site suggests a tower was there at least as early as 1358, and perhaps as early as 1320 as a defense against Scottish raids. It was a pele (pronounced peel) tower connected to a main hall, built from finely dressed stone masonry. Pele towers were typically free-standing towers that stood high above the landscape, providing a stony defense against invaders. The presence of a pele tower was also a status symbol for those who owned English manors. What remains of Radcliffe Tower today is a structure that is a jagged shadow of its former self, standing today about 20 feet high, and sixty feet on its longest side. In its heyday, it had the classic profile of a fortified manor, complete with castle-like crenellations.

“Old Radcliffe Tower,” by James ‘Clock’ Shaw (1830). Bury Art Museum.

The parish church of St. Mary and St.Bartholomew in the 19th century.

The nearby Church of St. Mary and St. Bartholomew in Radcliffe was built/rebuilt at the same time as the tower. The church is built over the site of an earlier church that dates back over 1000 years. The church is part of a living faith community today.

The structures were owned by those referred to by British and family historians as the Tower Radcliffes. Over the next four centuries, the power and fortunes of the Tower Radcliffes and their branches rose to prominence from the MIddle Ages into the Tudor period. Yet, as kings and queens came and went and the role of feudal power was transformed, their fortunes also waned. The descendants of the Tower Radcliffes produced 14 earls, one viscount, five barons, seven knights of the Garter, one lord-deputy of Ireland, two ambassadors, several baronets and knights of the Bath, along with many privy counselors, warriors, statesmen, and several high-sheriffs of Lancaster. Below is a brief look at a selection of individual Radcliffes, focusing on the Tower and Ordsall Hall families, and the branches that contributed to Ratliff/Ratcliffe settlement in America. But first, let’s have a look at the early origins of the family name and location.

Before the Norman Conquest

For the first three seasons of A.D. 1066, a group of farmers and herders along the River Irwell lived their lives as they had for time immemorial among the moors and swamps south of the village of Bury. The brush and grass along the relatively narrow river was periodically interrupted with cliffs of red sandstone on its southwest side. These Anglo-Saxon agrarians of the 11th century lived in timber-post houses with thatched roofs. They survived on a diet dominated by small, round loaves of bread often served with leeks, cabbage, beetroot and other vegetables. Their primarily vegetarian diet was often supplemented with mutton, beef or pork in a “briw,” or pottage stew made with wheat or barley. It was cooked over an open fire built in the center of a wattle-and-daub, thatched roof house’s living area. There were no chimneys, so the fires for briw and warmth often filled the living areas with smoke. The residents knew the threat of contaminated water. The solution was that everyone, even the children, mostly drank beer.

Typical Anglo-Saxon Dwelling

The closest major town was where the River Irwell met the River Irk. Today, it’s the central part of the city of Manchester. Until the autumn of 1066, the residents of the area knew Harold Godwinson as their king. Harold was crowned following the death of Edward the Confessor earlier that year. The area around the red cliffs of the Irwell was divided into one “hide,” or household, owned directly as a personal royal manor owned by King Edward, and another to the Salford Hundred, also under Edward’s control.

For 11th century Anglo-Saxon peasants living along the Irwell, the village was their world. England’s administrative center of Winchester was far away from the family, faith and hearth of the village near the red cliffs, just as it was in hundreds of villages across England. In villages like this one, life was lived in community rather than “society.” That is, social norms guided behavior more than laws, and the people bonded over what they had in common and the land they lived on.

The Old English language they spoke has been described as “coarse and gravelly, like waves crashing on a shingle beach.” Many words from their Old English survive today as pleasingly tough and blunt, hard and quick: womb, earth, sea, ship, air, sky, and forgive.

At the time, England was generally prosperous. A central feature of their economy was sheep. This animal was good for many things. Ewe’s milk was a strong source of nourishment, and mutton was a welcome source of protein. Their wool provided clothing, and their fat provided tallow for candles. Each family needed a modest plot of land to produce food. Essentially everyone pitched in for the arduous task of plowing. A family doing well for itself had a few acres for their vegetable and grain crops. The word “acre” being an Anglo-Saxon word for the amount of land a yoke of oxen could plow in one day.

After a day of baking bread, tending sheep, grinding grains and tending crops, the people of the village would often gather in the feasting hall. Around the hearth in this large room, they would drink, laugh, eat, tell stories and drink some more. Stories were told and retold.

Hwæt! (Attention!)

At this, the listeners in the glow of the fire would point their faces to the storyteller. An exciting and familiar story was about to unfold.

We Gardena in geardagum, (Praise of the prowess of folk-kings)

theodcyninga, thrym gefrunon, (of spear-armed Danes, in days of yore)

hu ða æthelingas ellen fremedon. (we have heard what honor the noble Saxons won!)

The story in this example was Beowulf. This epic poem begins in a mead hall, not unlike the one where the listeners were resting. In the story, the monster Grendel is wreaking havoc. Grendel is slain by the hero, Beowulf. The monster’s mother then attacks the mead hall to avenge the death of her son. Beowulf is later mortally wounded in the fighting. Like the hero of epic poems through the ages, from Gilgamesh to Hercules, the hero travels great distances and proves his strength against incredible odds. J.R.R. Tolkien was a leading scholar of the poem. He remarked that Beowulf, originally an oral tradition, has a richness to it that “is in fact so interesting as poetry, in places poetry so powerful, that this quite overshadows the historical content.”

These and other stories told around the hearth filled the minds of the people of the village, just as the briw and bread filled their stomachs. Like Tolkien’s Bilbo and Gollum from Lord of the Rings, the Anglo Saxon villagers also enjoyed a tradition of riddles, like this one from the Enigmata, written by Aldhelm, the Bishop of Sherborne:

Who would not be amazed by my strange lot?

With my strength I bear a thousand forest oaks,

But a slender needle at once pierces me, the bearer of such burdens;

Birds flying in the sky and fish swimming in the sea

Once took their first life from me;

A third of the world is held in my power.(Answer: Water)

Life here was marked by a highly developed hierarchy. To oversimplify, at the top was the king, followed by the earls or nobles. Below them were the non-noble landowners called thanes who owned much more land than regular peasant farmers. The thanes were also considered the warrior class who were in the king’s service. Next were freeman, called “ceorls” (pronounced churls), who were considered the peasantry. The ceorl’s personal wealth could vary quite a bit, but their social position was found in this broad category. At the bottom were slaves, who were most commonly in that position as a criminal penalty. However, some who were impoverished were forced into selling themselves and their families into slavery to escape starvation and other ravages of medieval poverty. The whole of England’s population was about two million at the time.

There was a limited amount of social mobility. Slaves could be freed by their masters. A ceorl may gain the ability to move up in social status through commerce and soldiery. If he was able to acquire five hides of land, or engaged over overseas commercial voyages in his own ship, he would be considered a thane. Thanes could become earls, and earls might even reach the status of royalty. Downward movement was also certainly possible. Though difficult, and usually generational, upward social mobility was easier in Anglo Saxon than in Norman society, where status was tied strongly to one’s ancestry.

The people of the area were known to each other by single Anglo-Saxon given names, like Cuthbert, Edgar, Audrey, Ethel, Wulfric, and Cynehild. They didn’t use surnames, but children often carried the names of their grandparents, a tradition carried among some of their descendants to this day. Instead of family names, they would sometimes carry “bynames” associated with their job, a distinguishing characteristic, or where they lived.

Bynames associated with a role could be very specific. Examples from the early 11th century include Girold “Furwatel” (Cake-Oven), or Luuignes “Scalarius” (Ladder-maker). Bynames based on characteristics could be much more colorful. Names recorded in the 1085 Domesday Book include the unflattering (Eysteinn “Meinfretr”/Harm-fart, the descriptive (Humphrey “Uis de Leuu”/Wolf-face), and the telling (Roger “Deus saluaet dominas”/God-save-the-ladies’). Bynames associated with places were pretty straightforward. It’s entirely possible that there were individuals who carried bynames that were an early form of Radcliffe based on their residence close to the Irwell’s cliffs, or because they quarried the cliffs’ sandstone. The family surname name would soon be adopted by both the commoners and noble alike.

The culture was deeply religious. Christianity had supplanted the pagan gods and rituals long ago. People in Anglo-Saxon villages were required to go to church more frequently. The church was the center of important rituals, such as baptism, that tied the Christian community together. It was also the place where they learned about how to interpret the world and their place in it.

A generation or so beforehand, the people were warily anticipating the end of the world. Archbishop Wulfstan of York had warned that the years around A.D. 1000 would usher in the time of the Antichrist, and the terrors of the Last Days. By 1066, the end of the world had not come. However, the Anglo-Saxon world, including this nook on the River Irwell, was about to undergo a dramatic political, religious and cultural shift.

In the weeks that followed the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066, the residents would learn that Norman/French forces under William, the Duke of Normandy, had defeated England’s Anglo-Saxon ruler. A new regime would soon transform their lives and culture. This included the changes in language through the introduction of French words, changes in the political structure, and the introduction of heritable family names. Over the next few centuries, serfdom, where individuals were legally and economically in subjugation of a lord, became a more prominent fixture. Serfdom replaced some of the loyalties and social restraints that once belonged to tribal Anglo Saxon culture. Serfdom itself eventually disappeared from English society by the end of the 15th century. Yet, through each of these societal changes, the family unit remained the most important basic unit of society, from Anglo-Saxon times through the early modern era summarized here. Peasant families, whether freemen or serfs attached to a manor, still raised their children, sought economic stability, and lived their lives punctuated with moments of pleasure and hardship.

Harold Godwinson swearing an oath on holy relics to William, Duke of Normandy, Bayeux Tapestry, (c. 1070)

Meet the New Boss: William the Conqueror

So, why did the Duke of Normandy invade England in the first place? William, Edward the Confessor’s first cousin, claimed that England’s childless king had at one point promised him the throne, and that the earl, Harold Godwinson, had sworn to uphold William’s claim to the throne. Yet, by the time of Edward’s death, all but one of England’s earldoms were ruled by Harold’s brothers, and his sister was Queen Edith. These family connections made him more powerful than the aging king in the final years of Edward the Confessor’s rule. As King Edward got older, he began promising his throne to a variety of people. On his deathbed he promised it to Harold Godwinson, who considered the king’s word good enough to release him from his oath to William. In response, William assembled a fleet and invaded England in 1066. Harold’s infantry could not defeat William’s cavalry at the Battle of Hastings. The king and three of his brothers were killed in the battle. William was crowned king of England on Christmas Day 1066.

One of William’s noblemen, Ivo de Tailbois, became tenant-in-chief of the area around Radcliffe. In 1085, a detailed survey of William’s kingdom was commissioned. Today, that survey is known as the Domesday Book. The area along the River Irwell where the Ratliff ancestors originated was indicated as “Radeclive” in the survey. The location was a naturally defensible location near a natural bend in the River Irwell that could act as a moat in case of attack. Perhaps for this reason it was held as a personal property of Edward the Confessor prior to the Norman invasion.

“Radecliue,” later Radcliffe, as it appears in the Domesday Book (1085)

Ivo’s grandson, Nicholas Fitz-Gilbert de Tailbois, was the first to adopt the name “de Radcliffe” indicating the area that was known from late 11th century by that name. Nicholas sought to establish himself as a man of the territory in an effort to win the hearts and minds of the locals. This was done in part by dropping the French name, Tailibois, in favor of the geographical byname. His reinvention as an Englishman approached completion by marrying the daughter of a Anglo-Saxon thane from a nearby area called The Booths. She is recorded in history as the “Lady of the Booths.” Soon, the French bynames were dropped entirely as the Radeclives/Radcliffes rose in influence.

William de Radeclive, Nicholas’ grandson built the first manor house here following the return of Richard the Lionhearted from the Crusades. William had participated in a rebellion against Richard’s chancellor during the king’s absence. In 1212, he was listed as one of “twelve trusty knights of the shire” in a survey. After Richard’s return, WIlliam became the first Radcliffe appointed High Sheriff of Lancashire.

Radcliffes and the Kings Edward

Richard of Radclyffe Manor (d. 1326)

One of the most famous scenes in movie history is set on September 11, 1297. William Wallace, the main character of the film, Braveheart, delivered an impassioned speech to a group of reticent Scottish warriors facing battle. He delivered his lines through a face painted with heavy streaks of blue, and with a sword longer than his torso slung over his back. As his horse impatiently cantered back and forth, Wallace encouraged the outnumbered men not to run away from the English forces opposing them. He roused the warriors with the words, “They may take our lives. But they will never take our freedom!”

Mel Gibson as WIlliam Wallace in Braveheart, Paramount Pictures (1995)

Of course, this speech never happened – at least not outside a Hollywood production. Wallace never said those words. Yet, the real Battle of Stirling Bridge depicted in the film and subsequent battles in the Scottish wars for independence were a turning point for both Scots and English. It was also a turning point for a man who embodies a watershed moment in the history of the Tower Radcliffe family. Sir Richard de Radclyffe was a leader among the English forces against the Scottish armies. As lord of Radcliffe, he mustered troops from the lands under his control. Doubtless that there were many archers, infantry and perhaps cavalry that Sir Richard led that were not manor-born, and whose descendants in later centuries would come to America.

A century and a half after Nicholas Fitz-Gilbert de Tailbois took the Radclyffe name, his descendants had increased in influence and land ownership in the Salford Hundred north of Manchester. At the cusp of the year 1300, Radclyffe influence was poised to transition from regional prominence to the ranks of England’s noble elite. Richard de Radclyffe (sometimes referred to as Richard the Seneschal), was lord of the Radcliffe Manor and senechal (chief administrator) of the King’s Forest of Blackburnshire, about 20 miles north of the tower. Richard raised a considerable number of soldiers from his domain to fight in the wars for Scottish independence alongside King Edward I (“Longshanks”). Richard and his Radcliffe militia were present at both the Battle of Stirling Bridge as well as among the many knights and their forces at the English victory during the Battle of Falkirk. Seven years after the English loss at Stirling Bridge, Longshanks was back in Stirling Castle, where he awarded Richard de Radclyffe “free warren and free chace” (permission to freely hunt) on a section of the king’s lands near his manor as a reward for his participation in the Scottish wars.

Three years later, the king was dead, and England soon plunged into chaos under his son, Edward II. During his reign, Richard was among the landowners and barons led by the Earl of Lancaster that were willing to directly oppose the king with personal military support. Through the backing of Radclyffe and many other landowners, Lancaster forced Edward II to relinquish power, making Lancaster effectively the ruler of England between 1314 and 1318. After the rebellious earl’s capture and execution, Radclyffe and some other Lancaster nobles escaped severe punishment by the king in the interest of reducing chances of further rebellion.

When he wasn’t administering the king’s forests or fighting Longshanks’ battles in Scotland, Richard de Radclyffe looked after the education and potential futures of his five sons and four daughters. The favor he received through service to Edward I inspired Richard to envision a period of prosperity for unified England, and the high role that Radclyffes could play. To that end, he encouraged his children’s education as land administrators, and their understanding of how to navigate the world of 14th century English politics. It paid off during the tumultuous but ultimately successful reign of Edward III. The subsequent tradition of Radcliffes/Ratcliffes attaining prominence attests to his forward thinking about the role the family could play in the development of the country. But before their day would arrive, the Radclyffes needed to survive the disastrous reign of Edward II.

Margaret Radclyffe, Lady of Bury (d. 1343)

Richard de Radclyffe’s third daughter, Margaret, was considered by historians as “one of the most remarkable women of her time.” Her husband, Sir Henry de Bury, was slain during a pitched street battle between the Radclyffes and other Lancaster loyalists against a group loyal to Edward II. After her husband’s murder, the killers looted Margaret and Henry’s manor and stole their horses. The violence was one of many similar instances connected to Radclyffe support of the Earl of Lancaster. Before his death, Henry had made arrangements for his lands to be held by Margaret until her death, instead of immediately passing to his heirs. After her husband’s death, Margaret took up the rulership of the town, becoming known as the Great Dame Margery, Lady of Bury.

This lawless period was captured in a Middle English poem called The Simonie, or Evil Times of Edward II. It was written in Middle English sometime between 1321 and 1330, about 50 years earlier than Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. The poem runs 545 lines. Ten are reproduced here in order to deliver insight to the state of English society and sentiment toward King Edward II during his reign. It also gives a sense of the language they spoke at the time:

|

Middle English (Original) |

Modern English |

|

Whii werre and wrake in londe and manslauht is i-come, |

Why have war and vengeance and manslaughter come into the land? |

|

Whii hungger and derthe on eorthe the pore hath undernome, |

Why have the poor suffered hunger and scarcity in this land? |

|

Whii bestes ben thus storve, whii corn hath ben so dere, |

Why have animals been starving, why has wheat been so costly? |

|

Ye that wolen abide, listneth and ye mowen here the skile. |

Those who will dwell here, listen and you may find the reason. |

|

… |

… |

|

Ac shrewedeliche for sothe hii don the kinges heste; |

Cursed indeed are those who have followed the king’s bidding; |

|

Whan everi man hath his part, the king hath the leste, |

Though every man is responsible for his role, the king is as well. |

|

Everi man is aboute to fille his owen purs; |

Every man is about to fill his own purse [with bribes]; |

|

And the king hath the leste part, and he hath al the curs, Wid wronge. |

And the king has played an active part – he has cursed all with corruption. |

|

And sende treuthe into this lond, for tricherie dureth to longe. |

And send truth into this land, for treachery has lasted too long. |

Many attributed the corruption and mayhem across England to the king’s own failings. Margaret felt she had enemies, both overt and covert, all around her. A famine followed the defeat of Edward II by Scottish forces under Robert the Bruce in 1314. As a result, landless men once employed as warriors became plunderers for hire, and continuous complaints of theft and violence flowed among rival manors. William Radclyffe and his brothers (Margaret’s siblings) participated in the lawlessness, conducting raids on rival manors, especially those whose lords were loyal to Edward II. This included breaking gates, doors, and windows, as well as looting, assaulting servants, and poaching.

Meanwhile, Margaret continued her attempts to stave off chaos in her town and protect her family at the same time. The fear of duplicity within Margaret’s own circle proved true when her oldest son was murdered by a mob. The town’s church rector was discovered as one of the ringleaders who fomented the killing. Soon afterward, Margaret brought in her elder brother as the new church rector so she could have an ally from her own “indomitable clan” by her side.

The Ordsall Hall Radcliffes

John Radcliffe and the Annus Mirabilis of 1345-46

The youngest of Richard de Radclyffe’s sons, Sir John Radcliffe, was the founder of the Ordsall Hall Radcliffes. He is also probably one of the most influential players in English history that you likely never heard of. Due to his father’s participation in the Earl of Lancaster’s rebellion against Edward II, he was able to join the service of the queen. This is due to the fact that Queen Isabella (nicknamed the “She-Wolf of France”) had a growing hatred of her husband, King Edward II.

John developed a warm friendship with Isabella’s son, Edward III, as he accompanied them to France. The English royal family held the Duchy of Aquitaine, south of the Loire River in France. This created an obligation for the English king (or his proxy, the queen) to pay homage to Isabella’s brother, King Charles IV of France. While in France, Isabella conspired to invade England and depose her husband in order to place young Edward III on the throne. John Radcliffe traveled with the invasion force of about 1,500 mercenaries back to England in the autumn of 1326. The widespread distaste for Edward II caught up with him for the last time, and his support evaporated upon Isabella’s arrival. Edward III was now king, and John Radcliffe was poised to play an important role in English national affairs.

Philippa of Hainault and her family seated under the canopy (c. 15th century)

One of John Radcliffe’s first duties was to ensure the safe passage of Lady Philippa from France to England for her marriage to Edward III. John acted as the king’s representative in the decision-making for the wedding in 1328. Queen Philippa proved to be a good political advisor to the king, convincing him that he should expand England’s commercial trade footprint in Europe.

To this end, John Radcliffe was sent to Flanders (today’s northern Belgium) to negotiate treaties with the wealthy trade cities there, including Ghent, Bruges, and Ypres. The treaties would provide a valuable alliance against France, and go a long way toward easing the impoverishment that the people of England experienced under Edward II. As a reward for his service, John brought Flemish craftsmen back to Lancashire to establish the textile industry there. Two centuries later, the area was the most famous textile center in the world, producing 32 percent of the world’s cotton goods.

John Radcliffe was appointed Knight of the Shire in Lancashire in 1340. His long friendship with Edward III continued into the Hundred Year’s War. Due to his familial connection with France’s Charles IV, Edward III asserted his right to the French throne upon Charles’ death. John Radcliffe was part of the king’s personal entourage of two knights, 12 esquires and 14 archers.

He proved his worth to the king on the battlefield, particularly in attacks against French forces in the cities of Caen, Crecy and Calais. For anyone observing John’s coat of arms, this list of battles would indicate his intimate association with Edward III’s annus mirabilis or “miracle year.” John, Edward III’s old friend and advisor, was among the 10,000 English forces that invaded Normandy in 1345, and began a scorched earth campaign across the French countryside. The English took the city of Caen on July 26, 1346 in a single day. This was followed one month later by the lopsided English victory in the Battle of Crecy. In this battle, the English were outnumbered two to three French soldiers to one Englishman. Yet, at the end of the day, losses were estimated between 40 to three hundred English killed. French losses numbered at least 4,000 killed, including 1,542 nobles.

The lopsided victory at Crecy was credited to the English’s effective use of the longbow and its archers. The non-aristocratic men of England were required to learn how to effectively use the longbow. Archers were well-paid, held in high regard and were a well-disciplined fighting force. In contrast, in France and other European countries, archers were often peasants with little training, given low pay, and held to low expectations. The English longbow wielded by yeoman farmers, could of course penetrate the armor of noble and non-noble alike. A company of longbow archers, unique to English forces at the time, could quickly send almost continuous devastating volleys of armor-piercing arrows into enemy forces.

John Radcliffe’s coat of arms. Note the bull’s head and the motto, “Caen, Crecy, Calais.”

After winning the Battle of Crecy, Edward III’s forces, including John Radcliffe and the men he brought with him from Lancashire, then proceeded to capture the city of Calais, a city adjacent to the narrowest portion of the English channel. The English held Calais as a critical strategic possession for the next two centuries. For his service to the king, the coat of arms for John and his descendants were allowed by the crown to bear the prestigious motto “Caen, Crecy, Calais” on the Radcliffe coat of arms.

After returning home from the battles in France, John’s life was at a crossroads. He could return to continue his prestigious military service with the king, setting a course for more titles and personal glory, or he could serve the people of his area. He chose to stay. Perhaps the reality behind the battles destined for legend were enough for him. John set about transforming the quiet villages of the area around Ordsall Hall, Radcliffe Tower and other areas around Salford into an economically thriving area via the newly-introduced textile industry. He also conducted a renovation and rebuilding of his manor, Ordsall Hall. It was the time of the Black Death. It was also a time when landowners were selling their properties and leaving many out of work. Sir John spent his final decade-and-a-half of his life improving the economic lives of those living in the Salford and Manchester area. He succumbed to the plague in 1361.

1908 Postcard of the Bull’s Head Inn near Ordsall Hall. At the time of Sir John Radcliffe, the inn accommodated merchants buying textiles in the region. Named “Bull’s Head” after the crest from the Radcliffe coat of arms. It was demolished in 1938.

James Radcliffe of Radcliffe Tower (d. 1410)

The man credited with the greatest lasting effect on the tower and town of where the family originated was James Radcliffe. James fought at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403 against the rebel knight, Henry “Hotspur” Percy. More than 6,000 lives were lost in the four-hour battle, including Percy’s when he took an arrow to the face after opening his helmet visor. King Henry IV survived, barely. The high death count was due to the fact that both sides were equipped with longbowmen. The bodies on both sides were so numerous that it was not certain for a time who had won the battle. Despite its short duration, it was one of the bloodiest battles fought on English soil. The battle was immortalized by Shakespeare in his play Henry IV, Part I.

The English chronicler John Hardyng’s (1378-1465) lengthy verse chronicle covers English history from Brutus through Hardyng’s own lifetime. Hardyng, who served in the household of “Hotspur” Percy, and was present at the battle of Agincourt and other important events of his day. Richard Grafton, who edited Hardyng’s manuscripts, continued his history down to the reign of Henry VIII. Harding’s chronicle mentions Sir Richard Ratcliffe as a loyalist and executioner to Richard III (r. 1483-85), which made its way into Shakespeare’s play.

Radcliffe manor was partially destroyed in the 1400s by Percy’s forces in their rebellion. The sacking of Radcliffe manor occurred while James was away supporting the king in fighting the rebellion. Afterward James was given the right to rebuild his manor, fortify Radcliffe Tower, and build the parish church. King Henry IV, the first English king since the Norman conquest whose primary language was English, sent a message to James de Radcliffe in 1403, following the Battle of Shrewsbury:

“Know ye that we have of our special grace granted for us and for our heirs, as much as is in us, to our beloved esquire James de Radclyffe, that he should rebuild his manor house of Radclyffe, which is held of us as of the Honour of Lancaster in capite, as it is said, with walls of stone and lime, to enclose anew, and within those walls erect a hall and towers so kernelled [crenelated] and embattled for a certain fortalice he may hold to him and to his heirs for ever, … Witness the King at the Castle of Pontefract the 15th day of August in the 4th year of our reign, by the King himself.”

If you visit the town of Radcliffe today, the remains of the tower and the parish church are largely the result of James Radcliffe’s architectural efforts.

Sketch of a “greatly decayed” 15th century tablet of James Radcliffe and wife Elena. The edges were chipped away for healing amulets and tokens of James’ saintly nature.

Battle of Agincourt: October 25, 1415

Seven years after James Radcliffe was given the go-ahead to rebuild and fortify Radcliffe Tower, one of the last great battles of the Middle Ages in which the Radcliffe family played a role took place. The Battle of Agincourt was one of many that occurred during the Hundred Year’s War, a series of armed conflicts between England and France over the rightful inheritance of the French throne. In 1415, negotiations between England and France had again broken down, and King Henry V asserted his claim to the throne of France by way of his great-grandfather, Edward III. What he really wanted was the return of certain French lands and a large dowry for marriage to marry Catherine, the young daughter of France’s King Charles VI. Henry V felt insulted by France’s counteroffer to his demands, and he set out to defeat the French king by force.

Roster of Radcliffe forces at the Battle of Agincourt

|

Surname |

Given name |

Status in 1415 |

Biography |

Retinue |

Total Troops |

|

Radcliff |

John |

Esquire |

John Radcliffe was the youngest son of James Radcliffe of Radcliffe Tower. John served in the entourage of the king’s second eldest son, Thomas of Lancaster (later Duke of Clarence). He may have fought also at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. He was knighted by Henry V on the Agincourt campaign after the army landed at Harfleur. |

John’s retinue consisted of himself, 5 men-at-arms and 18 archers. A portion spent the battle in the garrison of Harfleur. |

24 |

|

Radcliffe |

Robert |

Esquire |

Of Lancashire. |

Robert Radcliffe’s retinue consisted of himself and 2 archers. |

3 |

|

Radcliffe |

Thomas |

Esquire |

? |

||

|

Radcliffe |

William |

Esquire |

son of Thomas Radcliffe |

Himself and 2 archers. |

3 |

|

Radcliffe |

Richard |

Knight |

Radcliffe received an annuity from Henry V, served as sheriff of Lancashire until 1430. |

Richard Radcliffe indented to serve with two men-at-arms and nine archers. All seem to have been present at the battle. He was also in command of a company of archers from Lancashire. |

12 |

Just as in the Battle of Crecy nearly seventy years beforehand, the English won a stunningly lopsided victory against the French at Agincourt. Longbowmen were again a significant factor. The muddy battlefield, crowding, and poor range of motion among the dismounted knights in suits of armor were other factors. The English lost between 112 and 600 men in the battle out of a force of 6,000 to 8,000 men (the vast majority of whom were archers). The French lost about 6,000 out of a fighting force of 25,000. Most of them were noble landowners. The British historian, Jonathan Sumpton, said that the list of noble dead at Agincourt “read like a roll call of the military and political leaders of the past generation.” The entire male lines of many French noble families were killed in the battle, with an entire generation of landed nobility wiped out across some regions of France. John and Thomas Radcliffe were knighted in the field by the king after the battle as an honor for the personal performance and the performance of those who accompanied them to Agincourt.

Life at the Radcliffe Manors

Though archery was a royally required pastime, military service was rare for those living around in the Radcliffe township and around Ordsall Hall. So what was life like during this period? In many ways, Radcliffe Tower and Ordsall Hall were typical of many manors and settlements around England.

The bad old days of widespread lawlessness and corruption during Edward II’s reign had been followed by the Black Death plague that decimated the population in the mid-1300s onward. But by the 15th century, their quality of life had begun to turn around. Highway robbers continued to be a problem, as were the usual issues of persistent disease and lack of medical and hygiene knowledge. Even so, even manor life was difficult and uncertain. For example, the Dutch philosopher/theologian Desiderus Erasmus (1466-1536) visited England a number of times. His notes provide valuable details about manor and common life. It must be noted that Erasmus was known for his acerbic but often truthful observations. His assessment of English country life during the Reformation did not escape his cutting wit. Erasmus did not have much good to say about the hygiene and livability of English manors. After visiting Ordsall Hall in 1499, he remarked:

“First of all, Englishmen never consider the aspect of their doors and windows: next, the chambers are built in such a way as to admit of no ventilation. Then a great part of the walls of the house is occupied with glass casements, which admit light, but exclude the air, and yet they let in the draft through holes and corners, which is often pestilential and stagnates there. The floors are in general laid with a white clay, and are covered with rushes, occasionally removed, but so imperfectly that the bottom layer is left undisturbed, sometimes for twenty years, harbouring expectorations, vomitings, the leakage of dogs and men, ale-droppings, scraps of fish, and other abominations not fit to be mentioned. Whenever the weather changes a vapour is exhaled, which I consider very detrimental to health.”

Erasmus cited the poor air flow, a salted (vs. fresh) meat diet, and unhygienic flooring to the frequency of a “sweating sickness” that was predominant in England and almost nowhere else, not even across the border in Scotland. A victim could expect to either die or fully recover from the disease after a full days’ cycle of shivers, delirium, severe pain in the neck and limbs, a feeling of coldness, followed by a sensation of being hot (accompanied by sweating), heart palpitations, and an irresistible urge to sleep. It afflicted every level of society, but there is some anecdotal evidence that it afflicted the rich more often than the poor. Some modern researchers have suggested it was a form of hantavirus.

Interior of Radcliffe Tower Hall, looking toward the tower (c. 1800).

Despite the harshness and uncertainty of medieval life, there was an ever-growing sense of English solidarity. Patriotism ran high, as did a convivial atmosphere that was a hallmark of life in the imagined past. English social life was increasingly governed by up to fifty church feast days and festivals throughout the year. These offered pleasant frames around a medieval life that was otherwise difficult in the best of seasons. From the late 14th through the mid-16th century, the idea of “Merry England” emerged, fed by joyful occasions that decorated the liturgical year with processions, pageants, games, and ample opportunities to feast all day and drink all night. The servile feudal system was quickly giving way to new opportunities for independent industries and growing towns. During the reign of Henry VII, England was prospering. Though inflation soared, so did wages. This was particularly true for those involved in spinning and weaving wool.

The last male in the direct line of the Radcliffes of Radcliffe Tower was born at the turn of the 16th century. In 1518, John Radclyffe, then a ward of Queen Catherine of Aragon, the first wife of Henry VIII, died. The Radcliffe Tower estate and the other Lancashire lands associated with his immediate family were willed to Robert Radcliffe, the First Earl of Sussex. Radcliffe Tower itself remained in this family for two more generations.

Radcliffe family ownership of Radcliffe Tower ended in 1561, when the Third Earl of Sussex, Thomas Radcliffe, sold the manor to Richard Assheton, Lord of Middleton. Thomas was the Lord Deputy of Ireland during a time of rebellion and Scottish uprisings. He also helped arrange the marriage of Queen Mary (“Bloody Mary”) to Philip II of Spain in 1554. He served Queen Elizabeth I as Lord Chamberlain, the most senior officer in the royal household by 1578. It seems the upkeep of the old Radcliffe country manor and tower was the furthest thing from his mind.

Margaret Ratcliffe and the Annus Horribilis of 1599

Though Radcliffe Tower had left the family, Ordsall Hall remained in direct possession of the Radcliffes for another century. In 1534, the Reformation swept England, instigated by Henry VIII’s quest for a new wife. The break with the Church of Rome was a watershed moment in English history, and marked a new period of tensions for Catholics in that country. This included the Radcliffes/Ratcliffes, who remained staunchly loyal to both Roman Catholicism and the Crown in the following generations.

John Radcliffe (1536-1589) of Ordsall Hall survived the scrutiny of Queen Elizabeth I’s spymaster, Francis Walsingham, who was searching for signs of a plot among English Catholic nobles against the queen. John signed onto an Association of Lancashire Gentlemen, formed to defend Queen Elizabeth against her Catholic rival, Mary Queen of Scots. During the late 1500’s John Radcliffe and his wife, Anne Asshawe, began raising a large family at Ordsall Hall. They had nine children. The eldest were twins, Alexander and Margaret born in 1573. A second set of twins, Thomas and Edmund, were born in 1587. John Radcliff died in 1589, when the nine children were all ages 16 and younger. In his will, John expressed his wishes that each would receive a good education, and perhaps study law, or otherwise enter life in academia at Oxford or Cambridge. He also expressed a hope that one of his progeny would also migrate to the New World: “I desire one of mye sons to proceed in the Civil Laws, within England, and, when he shall be of ability to travel, to go beyond the seas, for his better furtherance in learning, and not to dwell and continue in this country; for a time to come and see his mother, brothers and friends, and not to tarry over here long.” Their widowed mother, Anne, remained at Ordsall Hall managing the large family and the estate with the help of the extended Radcliffe family and the help of friends in the royal courts and military.

The twins Alexander and Margaret, inseparable companions as twins frequently are, were introduced early in life to the royal courts. They met Queen Elizabeth for the first time at her residence, the Palace of Whitehall. The palace was known for its high fashion, and continuous parade of England’s rich and beautiful. Yet, when the children, Alexander and Margaret arrived, they caused a bit of sensation. They looked so much alike, and the gallants and ladies alike remarked about their “striking physical beauty.” Queen Elizabeth noticed that Margaret wasn’t just another pretty face, She was full of wit, a joy of life, and shrewd judgment. After this meeting, the queen claimed Margaret as a Maid of Honor for her privy chamber, and quickly became Elizabeth’s favorite.

Margaret spent her days reveling in the intrigues and romances of the palace, and taking up equestrianism with her fellow merry friend, Anne Russell. She was courted by Henry Brooke, the 11th Baron of Cobham, which resulted in some palace drama among other ladies of the Privy Chamber that were rivals for the relationship. The press kept an eye on her as a minor celebrity in the palace, tracking her seemingly charmed life: “Yesterday did Mistress Radcliffe weare a whyte satten gown, all embroidered, rich cutt upon cloth of silver that cost 180 pounds…” reported one observor of daily life in the court.

It’s likely that Margaret Radcliffe met William Shakespeare. She and her peers were documentably familiar with his plays. Since the queen did not attend the theater, the plays were performed regularly at the palaces, and as a maid of honor Margaret would have been able to attend regularly. Margaret’s beau, Henry Brooke, publically complained to Shakespeare that the eponymous character in the play, Sir John Oldcastle, played as a fat, vain, and boastful knight, was named after his ancestor, and that he did not want his own name associated with the character. Shakespeare loved the character, and changed it in subsequent plays to “Falstaff.” The character Falstaff reappeared in a few of Shakespeare’s plays, including Henry IV and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

In the meantime, the Oldcastle/Fasltaff controversy took on a life of its own, and Henry Brooke became equated with the Falstaff character in the English public eye anyway. This was an inside joke in the Radcliffe family circles as well, evidenced by a letter in which the Earl of Essex teased Alexander Radcliffe (Margaret’s twin) that his sister “is maryed to Sr. Jo. Falstaff.” Margaret and Henry were still only courting, but everyone understood the reference. Not unlike Falstaff, Brooke’s affections were fickle, and they soon turned away from Margaret to Lady Frances Kildare.

Such were the comedies and dramas of court life Margaret enjoyed in the waning years of the 16th century. But multiple tragedies were about to strike the family. In August 1598, when Margaret was 25 years old, her younger brother William was killed in battle at Blackwater Fort in northern Ireland. Several months later, in 1599, her younger twin brothers, Edmund and Thomas both perished from a fever while with a military garrison in Flanders. They were twelve years old. Then, almost exactly one year after William’s death, Margaret’s beloved twin Alexander died after being wounded in the Battle of Curlew Pass in northwestern Ireland.

“Sir Alexander Ratcliffe, although he was, in the beginning of the skirmish, shot in the face, yet continued to spend all his powder upon the enemy, and, no supply coming unto him, prepared to charge them with a small number of such choice pikes, as would either voluntarily follow him, or were by him called forth by name from the body of the vanguard. But, before he could come to join with them he had the use of a leg taken from him. With the stroke of a bullet, by which ill fortune he was forced to retire, sustained upon the arms of two gentlemen, one of which, receiving the like hurt, died in the place, as did also himself soon after, being shot through the body with a bullet…There died Sir Alexander Ratcliffe, of whom cannot be said less than that he hath left behind him an eternal testimony of the nobleness of spirit which he had derived from an honourable family.” (Tracts Relating to Ireland by John Dymmok)

The queen herself broke the news to Margaret that Alexander had died. His death proved to be the final blow that threw Margaret into a deep depression. She left Queen Elizabeth’s court in order to mourn her brothers’ deaths at home in Ordsall Hall. Reports reached the queen that her favorite privy maid was doing very poorly in the home that was once full of happy memories of Alexander and her younger siblings. Queen Elizabeth decided she wanted Margaret attended to by the palace physicians. The queen also wanted to see her personally. When Margaret arrived at the palace, the queen and her attendants were surprised to see that Margaret was a mere “ghost” of her former self. A letter from an observer preserved impressions of Margaret’s condition at the time of her death in November 1599:

“There is news besides of the tragycall death of Mistress Ratcliffe the Mayde of honor, who ever synce the death of Sir Alexander her brother hathe pined in such strange manner, as voluntarily she hathe gone about to starve herself, and by the two days together hathe receivyed no sustinence, which meeting with extreame greife hathe made an end of her Mayden modest days at Richmond uppon Saterdaye last, her Majestie being present, who commanded her body to be opened and found it all well and sound, saving certyne strings striped all over her harte.”

At the queen’s order, Margaret was given a funeral at Westminster Abbey fit for a lady of much higher rank. Elizabeth I also asked the famous writer, Ben Jonson, to write an acrostic memorial poem for her burial marker:

Marble weep, for thou dost cover

A dead beauty underneath thee,

Rich as nature could bequeath thee:

Grant, then no rude hand remove her.

All the gazers on the skies

Read not in fair heaven’s story

Expresser truth or truer glory,

Than they might in her bright eyes.Rare as wonder was her wit;

And like nectar ever flowing:

Till time, strong by her bestowing,

Conquered have both life and it.

Life whose grief was out of fashion

In these times. Few have so rued

Fate in a brother. To conclude,

For wit, feature, and true passion

Earth, thou hast not such another.

At Margaret’s death, only Anne and John remained of the nine children. Anne passed away less than two years later, in 1601. Only John was left as the remaining child and Radcliffe heir of Ordsall Hall.

The deaths of the sons and daughter of the Ordsall Hall Radcliffes at the beginning of the 17th century was a harbinger of the fortunes that the aristocratic Radcliffes would endure over the coming decades. This included the Radcliffe Earls of Sussex. The second and third Radcliffe Earls of Sussex were among the hardest working and most influential nobles in 17th century English government. Yet, the office went extinct by 1643, when Edward Radcliffe, the 6th Earl of Sussex, died penniless and childless.

Some cousins of the Tower and Ordsall Hall Radcliffes were the relatively short-lived Earls of Derwentwater. In the late 1600s, the Radcliffe Barons of Derwentwater experienced a relatively quick rise and fall when Francis Radcliffe was raised to the status of Earl under Charles II in 1688. His son, Edward, became the second Earl of Derwentwater. At 32, he married 14-year-old Lady Mary Tudor. She was the daughter of King Charles II and his scandalous relationship with Moll Davies, an actress and singer. Their son, James Radcliffe, the 3rd Earl of Dewentwater, was beheaded on Tower Hill on February 24, 1716. His execution at age 26 was a result of his reluctant participation in the Jacobite uprising that challenged the installation of King George I. The Derwentwater lands were confiscated, and the earldom was formally retired. His brother, Charles, claimed the de jure title of earl. In exile, he worked as a private secretary for Charles Edward Stuart, also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, the “Young Pretender” to the English throne. This last Radcliffe claimant of the title “Earl of Derwentwater”’ was captured at sea smuggling arms to Scottish troops in 1745. He was beheaded at the Tower of London in December 1746. This was nine months after Bonnie Prince Charlie’s defeat at the Battle of Culloden Moor, which marked the end of the Jacobites as serious challengers to the English throne. By this time however, the Ratcliffe/Ratliff family lines of today had been established for generations in America.

The migration of the main groups of Radcliffes to America has its roots in the English Civil War (1642-1651). In fact, the nature of religious freedom, the roots of the Revolution and the tradition of distrusting the government in America also finds its roots in the English Civil War. The causes of the English Civil War and the ways it unfolded is complex. In short, a conflict emerged between King Charles I and Parliament over a number of issues outlined below. The English Civil War is relevant to this history for a number of reasons. First, it shows how the fortunes and influence of the noble Radcliffe lines declined in the wake of anti-Catholic sentiment. This is also integral with understanding the context in which the earliest members of the family moved to the New World, including their heritage as Catholic royalists. Almost all Radcliffe/Ratcliff groups that went to America, including Catholics, Quakers and Protestants, settled first in Maryland. This colony was established as a Catholic alternative that offered some of the first footholds of religious freedom that we enjoy in the United States today. Understanding the English Civil War can also lend insight into the core issues behind the American Revolution, which revealed revolt against the king by his subjects as a modern possibility. There were crucial themes in the English Civil War that resurfaced in the Revolution, including taxation without representation, and a king who was out of touch with the needs of his people. Here is a quick outline of the causes of the English Civil War in a few paragraphs:

The source of Charles I’s widespread opposition can be encapsulated in one sentence spoken by the king: “I mean to be obeyed.” While the context of this remark has to do with the imposition of the king’s revised Prayer Book on Scottish churches, it describes in a nutshell many of the attributes of Charles’ rule that roused his opposition and led to his downfall. The quote shows the king’s unilateral tendencies toward his relationship with Parliament, and his lack of willingness to embrace the interests of the people he was ruling. This both frightened and infuriated many who supported the monarchy as an institution, but not the style and actions of Charles I.

Charles I by Gerrit van Honthorst (1628)

The king was tone-deaf to societal shifts taking place in England that ran against his vision for the kingdom. Among those shifts were strong currents moving through religious worship in the country. There was also a disconnect between Charles I and his opponents regarding political ideals about the rule of law, representative assembly and the role of the monarchy.

The dissolutions of Parliament and adoption of Personal Rule from 1629 onward were viewed by many as a form of tyranny. Specifically, it violated the idea that the king was beholden to the rule of law, as asserted in the Magna Carta, signed in 1215. Ignoring Parliament alarmed those who saw representation in the legislative body as a sacred right and a political instrument to stave off tyranny. In contrast, Charles viewed the Magna Carta as, in the words of one loyalist,“a chain to bind the king from doing anything.” To the kings’ opponents, England was unique because it had progressed beyond medieval ideas regarding the absolute rights of rulers that still prevailed in European kingdoms. Some specific abusive policies stirred up resentment. Charles I extracted forced loans from nobles under threat of imprisonment. The king also bestowed monopolies that forced many tradesmen out of business or into service of the monopoly.

Alongside political factors there were religious factors that stoked passionate resistance. Charles I dismissed the rising popularity of Puritanism popular across England. His reaction to this religious challenge was the attempted suppression of Puritanism in the kingdom’s churches. Puritanism emphasized a more stoic and reserved approach to Christian faith. As Calvinists they believed that God had chosen some for salvation and others not, and one could not know with certainty whether one was saved until the Judgment. Outward signs of election were holiness and piety, which manifested itself in churches that lacked elaborate adornment. Their style of worship also offered much more simplified church services than the ritual-heavy practices held over from before the Reformation. Among the Puritans, adherence to Calvinism was wrapped together with their strong sense of religious loyalty to Reformation principles. The further the church shed the decorative and ritual trappings of Catholicism, the closer they felt they were to true Christian worship.

On the other hand, Arminian Protestantism of the type preferred by Charles I repudiated Calvinistic ideas about the role of predestination and election, arguing instead that free will played the greatest role in the salvation of the believer. The Arminianism of Charles I was accompanied by a type of ecclesiastical ceremonialism and more elaborate ritual and decoration that his opponents equated with “popery”/Catholicism. Opposition ran high against any sign that the Catholic Church was making religious or political progress in England. Though the king was not Catholic, his willingness to work with English Catholics, and his advancement of what were perceived as Catholic stylings in the churches, raised suspicions and stoked opposition. The suspicion that Charles I was at least susceptible to Catholic influence was exacerbated by the fact that he had married Henrietta Maria, the French king’s Catholic daughter. The queen consort openly practiced Catholicism, and the king was conspicuously devoted to her, which also raised Puritan suspicions. Among the alarm bells was the fact that in 1632, Charles I had carved out a large portion of the upper Chesapeake Bay claimed by the Virginia colony and gave it to Lord Baltimore, a Catholic convert. The new colony was named Mary Land, in honor of the king’s wife. It was a safe harbor for a religious minority viewed with suspicion by the powerful Puritans. Furthermore, the king had also made peace with France and Spain. As a result, English Puritans stood to lose the commercial connections they had with their Calvinist counterparts in Protestant countries left out of these treaties.

As Catholics loyal to both their church and the king, the Radcliffes were natural enemies of the Puritan/Parliamentary forces who wanted Charles I removed. The family’s fortunes had diminished in the years leading up to the civil war, and Ordsall Hall itself was physically reduced to a more manageable size. There were a number of those who lived at Ordsall Hall who played an important role in the conflict. This includes the lord of the manor and his 15-year-old son who died in London after being wounded in battle.

Great societal changes were afoot in England during the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period. It was in the midst of these changes that the groups of Radcliffes/Ratcliffes that became the founding families of the name in America took shape. This included Catholics, Protestants and Quakers. Over the centuries, the Radcliffe/Ratcliffe name proliferated, particularly in northern England. The carriers of the name to America are defined by a few specific individuals and family groups. Counted among them are Catholic Radcliffes associated with the noble families from the Manchester area, Quaker Radcliffes of Rossendale and others from York, Sussex and other localities.

Molyneux Radcliffe, Royalist Musketeer

Molyneaux Radcliffe straddled the worlds of both noblemen or a commoners. He also toggled between the roles of family man and warrior. He is noted for his service and gallantry in battle, but records show a strong family life. It’s through his line that we also inherit an insightful glimpse at early Radcliffe life in the New World. His life and family offers a chance to observe the continuity of life between England and America.

Molyneux Radcliffe was born in 1599, during the annus horribilis of the Ordsall Hall Radcliffes. Exactly who his father and mother were remains a mystery, but records do show that he was a member of the Ordsall Hall manor family. A central requirement of men raised in the manor was that they serve in the military on behalf of the manor. In this case, Molyneux was noted for his devotion and bravery in the English Civil War in the service of James Stanley, the 7th Earl of Derby (AKA Lord Strange).

One initial item of interest is his name. First names in England typically came from surprisingly few choices. Serf records only show about three dozen male names, and twenty female names used in several villages. These were usually Norman names, and often that of a saint. “Molyneux” was not among these. Rather, his first name was the surname of a family closely associated with the Tower/Ordsall Hall Radcliffes for many years. Any number of scenarios could explain the unique name. However, there are no available records that offer definitive clues.

The first time Molyneux Radcliffe enters the record is on his wedding day, May 5, 1631. He married Bridget Finett at St. Margaret’s Church on the grounds of Westminster Abbey. It should be noted that anti-Catholic sentiment was running high in the 1630s. The Radcliffes of Ordsall Hall, including Molyneux, were Catholic. Since 1559, it had been illegal for Catholic priests to say mass in England. The same year Molyneux and Bridget were married in St. Margaret’s Church, a Catholic priest was arrested for performing mass at Lady Shrewsbury’s residence at Piccadilly Hall a mile or so away. Three years later, five Catholic priests that were secretly working within the church where Molyneux and Bridget were married were indicted for high treason.

In 1635, Molyneux and Bridget celebrated the baptism of their first child, Emmanuel. They were living in the market town of Ormskirk, about 30 miles west of Ordsall Hall. Emmanuel would grow up to be one of the earliest and most interesting Ratcliffes that migrated to America.

Just two years Emmanuel was born, Molyneux was on deployment with the Earl of Derby’s army. In addition to his holdings in England, James Stanley, styled as the Earl of Derby and Lord Strange in England, was also the Sovereign and Liege Lord of the Isle of Man, or in the Manx language, Yn Stanlagh Mooar (The Great Stanley). Molyneux is listed as James Stanley’s bodyguard during a ceremony that occurred on July 6, 1637.

Prior to the 18th century, the Isle of Man had a calendar full of feast days and fairs. Methodism suppressed many of the celebrations in the 18th century that were derived from the variety of Manx cultural influences, such as the Scandinavian, Irish Gaelic, Catholic and even pre-Celtic traditions. The most important, which has survived to this day, is Tynwald Day. The ceremony dates back more than 1000 years to a Viking tradition. Tynwald is the Manx name for the island’s parliament.

The point of Tynwald Day was (and is) to publicly read aloud the new laws that were passed over the course of the previous year. The ceremony grew more elaborate over time. By the time of Molyneux Radcliffe and James Stanley, there was a great deal of pomp and circumstance associated with the ruler’s procession from the ancient Rushen Castle for the annual “Thing.” A “thing” in the Norse-influenced Manx language, is the word for a gathering of the community. Things would include trade and religious activity, often with booths set up for traders doing business at the gathering.

The civic ceremony was presided over by the rulers, legislators and judges (called deemsters). The Lord of Man would proceed behind a chosen bodyguard carrying the “Sword of State.” The same large sword has been used in the ceremony from the 1400s until today. The entourage would arrive at a tiered mound, where the Lord of Man would then preside over the reading of the laws by the deemsters. This ceremony has survived until today. Queen Elizabeth II marched behind the Sword of State as the current Lord Proprietor in 2003. Molyneux is singled out in the record as being identified as Lord Strange’s bodyguard, so it is possible that he was the sword bearer during the Tynwald Day ceremony in 1637. Regardless, being a member of James Stanley’s personal detail would be a high honor and personal show of confidence. It should be noted that the Radcliffe surname reached the Isle of Man in the mid-late 1500s. Some Ratcliffe families in the U.S. claim ancestry from these Manx Radcliffes.

On May 2, 1644, Molyneux’s daughter was baptized in Ormskirk. She was named Bridget after her mother. The name, Bridget, would be passed down from mother to daughter in the Maryland colony for four generations. There was not much time for a peaceful homelife at that time, however. By February that year, Molyneux Radcliffe was defending the last royalist stronghold in northwest England against the parliamentary army. Lathom House was the family seat of the Earls of Derby since the late 14th century. In early 1644, Lord Strange was away from his family home fortifying his dominion on Isle of Man against a possible Scottish invasion.

His wife, Countess Charlotte, took on a leadership role in preparing for the siege. Molyneux Radcliffe was among the 300 cavaliers in the service of Countess Charlotte tasked with defending Lathom House against Parliament’s army of 2,000. The leader of the anti-royalist forces, Sir Thomas Fairfax, saw the earl’s absence as weakness in property’s defenses. He wasn’t counting on a strong and capable defense by Charlotte and her cavaliers. Fairfax offered terms of surrender, but Charlotte refused as a matter of safety and honor. Instead, she filled Lathom House with enough supplies to endure an extended siege.

At the time, Lathom House was a timber-frame castle, described as follows: “In the centre was a lofty tower, called the Eagles’; it had two courts, for mention is made of a strong and high gateway before the first. The whole was surrounded with a wall two yards thick, flanked by nine towers, and this again guarded a moat eight yards wide and two deep.”

In March 1644, Fairfax’s troops attacked the walls of the fortified compound, resulting in the loss of 30 “Roundheads” killed and six prisoners taken. On April 1st, Fairfax pounded the walls of the wood-framed castle with cannons filled with chain-shot and iron bars, to little effect. Four days later, Molyneux and four other captains charged out of the castle from a concealed gate and forced the enemy out of their entrenched positions around the castle. In the process, they killed about sixty of Fairfax’s army, disabled the cannons, and captured about sixty weapons. As for Molyneux, it was recorded that “in a sally in which the besiegers were driven from all their works and batteries, with three soldiers, the rest of his squadron being scattered engaging the enemy, cleared two sconces, and slew seven men with his own hand.”

At a signal from Lathom House’s central tower, Molyneux and his troops retreated back into Lathom House before parliamentarian reinforcements could arrive.

Siege of Lathom House by W. Topham, 19th century

Fairfax intensified his siege with more cannon fire and attacks on the castle. He also offered another chance for Lady Charlotte to surrender. Eyewitnesses recall her telling the messenger who carried the offer:

“Thou art but a foolish instrument of a traitor’s pride: carry this answer back to Rigby’ [scornfully tearing up the paper as the messenger watched]. Tell that insolent rebel he shall neither have persons, goods, nor house. When our strength and provisions are spent we shall find a fire more merciful than Rigby; and then, if the providence of God prevent it not, my goods and house shall burn in his sight; and myself, children, and soldiers, rather than fall into his hands, will seal our religion and loyalty in the same flame!” Hearing this, the soldiers under her command broke into a cheer, vowing “We will die for his Majesty and your honor! God save the King!” (History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster by Edward Baines)

The siege was lifted in late May as royalist relief troops were reported as heading toward Lathom House. Countess Charlotte and her children peacefully left Lathom House and retreated to the safety of the Isle of Man. The house itself was left in the care of a royalist military garrison. An accounting of the parliamentary cost of the siege provided these numbers: Shot at the house: 109 cannon, 32 stones, and four grenades, at a cost of a hundred barrels of gunpowder. Five hundred parliamentary troops were killed and 140 wounded. Royalist losses included five or six men in total.

Molyneux Radcliffe fought in the Earl of Derby’s army until he was killed storming a fort in 1645. The Earl of Stanley remarked in his journal that Molyneux “merits perpetual remembrance for his most valiant services. He commanded the van in twelve sallies, and always brought off his men with success; but at last this gallant gentleman had the misfortune to be slain in storming a fort of the enemy’s.”

Molyneux was not only remembered by the Stanley family. His heroics at the siege of Lathom House also made it into fiction two centuries years later when there was a renewed public interest in the English Civil War. He appears as a character in The Leaguer of Lathom by William Harrison Ainsworth. John Brougham, the Irish-American dramatist and comedian known for lampooning romantic melodramas, published a short romance story called Love and Loyalty in 1855 that portrays Molyneux as a protagonist. A bit of Molyneux’s dialogue in this story perhaps inspired the classic “tis but a scratch” line uttered by the Black Knight in the movie, Monty Python and the Holy Grail. In the story, Molyneux penetrates the castle Lathom House during the siege to fulfill a promise to his love that he would come to her on that day:

“At that instant, several shots were heard in quick succession, followed almost immediately by a shot from the battlements of the Castle. And before either [Countess Charlotte and Radcliffe’s fictional love, Elinor] had time to breathe their thoughts, the door burst open and the noble Molineux Radcliffe was in the arms of his beloved one. The shock was almost too much for her, but, with a powerful effort, she checked the sensation that was creeping through her frame.

“My own, own love,” said he, “look up, I’m here, my pledge is redeemed, my promise fulfilled, I’m here, here to live or die with thee.’ …

“But see, dearest, you are wounded,” exclaimed Elinor, in alarm, perceiving traces of blood on his doublet.”

“A scratch, beloved: a mere scratch,” continued Radcliffe, “for which believe me, I returned a deeper [wound]. …”

Molyneux is also a close friend of the main character in the 1902 novel, Nicholas Mosley, Loyalist, Or, What’s in a Name? written by Rev. Ernest Letts and his daughter, Mary Felicia Simeon Letts. This book describes Molyneux as an “odd looking boy, with thick red hair that stands nearly straight on end as it is possible for human hair to stand, and a face so freckled it would be difficult to say what the original colour had been.” Where Brougham’s short story can be overwrought by today’s standards, Letts’ lively novel is very readable.

Religious Roots of Migration to America

Throughout the 1600s, England was fertile ground for Protestant groups that disagreed with the Church of England over theology and forms of worship. Some remained nominally within the Church, such as the Puritans. Others broke radically from the church’s structure and beliefs. The “dissenters” came in a wide variety. They included the politically-minded Levellers. This groups believed that everyone has the capability to acquire salvation through the common gift of reason, and that the economic rift between rich and poor should be eliminated (levelled). The political implications of their theology argued that kings are not divinely appointed, and that everyone should be treated equally before the law.

Others were more spiritually-focused. This includes groups like the Muggletonians. This group perhaps inspired the ideas of “Muggles” in the Harry Potter books through their intense focus on materiality over the spirit world. The Muggletonians began as an apocalyptic sect conceived in the minds of John Reeve and Lodowick Muggleton. It appealed to middle-class merchants and artisans. They disbelieved prayer and eschewed religious services, practicing their radical non-conformist beliefs by meeting in alehouses for singing and theological bull sessions. Some of their conclusions attributes are seen today in Mormonism, including the idea of God as anthropomorphic, a glorified man, and the “two seeds” theology of the creation of humanity, where one seed drew believers toward faith, and the other seed drew humanity toward wickedness. Muggletonians persisted in England into the 20th century.

The arch-nemeses of the Muggletonians were the Quakers. The two sects engaged in a war of words during the English Civil War and beyond. An example of this is from the prominent Quaker and found of Pennsylvania William Penn, who let loose on the Muggletonian founders: “From the most primitive times there has not appeared a more complete monster than John Reeve and Lodowick Muggleton, brethren and associates in the blackest work that ever fallen men or angels could probably have set themselves upon.” The pamphleteering battle between the two groups was lopsided, as Muggletonians only had about 1,000 followers, while Quakers numbered in the tens of thousands in 17th century England.

The Quaker movement began with George Fox, the son of a relatively wealthy weaver. He grew up in a strongly Puritan environment, and had a natural disposition toward piety. The English Civil War was in full swing when he began his outdoor preaching travels. He drew followers through both his scripturally-based sermons on the simplicity of a Christian life, as well as his ability to frame his message with intense personal experience. In 1650, he was jailed for “blasphemy,” with a judge deriding him as a “Quaker” because he called them to “tremble” before the word of the Lord. The year 1652 was a watershed moment in his ministry. He had a vision on Pendle Hill in Lancashire, about 40 miles north of Radcliffe Tower. In the vision, he saw a crowd of people coming dressed in white raiment coming to Christ. He interpreted this as a great number of people receiving the spirituality that he was professing. Within eight years, there were about 50,000 adherents. By 1680, the consisted of about 1.15% of the total population of England and Wales.

Pendle Hill above the mist, 2007

A number of Quaker beliefs were considered radical at the time. This included the idea that men and women were equals, and that women could speak out in worship services. Quakers emphasized that believers should talk, behave and live comprehensively according to faith and love. Their religious nonconformity invited persecution. This included outlawing religious services and jailing adherents. Quakers present in the American colonies suffered at the hands of Puritans through banishments and imprisonments. In 1660, Mary Dyer was among four Quakers put to death for defying anti-Quaker laws in the Massachusetts colony. Quakerism emphasizes the personal encounter with God: